Payment systems are the lifeblood of economies across the world, thanks to their ability to accelerate development efforts. The World Bank’s FINDEX report found that the most common use for an account is to make or receive a payment, followed by saving and borrowing. According to FINDEX, in developing economies, 36 percent of adults received a payment into an account. Of those, 83 percent also reported that they made a digital payment. Almost two-thirds of payment recipients used their account to store money, about 40 percent to save money, and about 40 percent to borrow money. These findings highlight the leading role that payment systems play in enabling financial inclusion.

Yet, at the same time, in many countries around the world, it can take days to transfer payments from the remitter to recipient, and transaction costs can often be very high. In addition, some countries lack their own domestic payment systems. This leaves them dependent on foreign payment systems that may be too expensive and exposes them to the risk of sanctions.

DPI is helping solve the challenges faced by traditional payment systems.

To overcome a number of policy challenges, and to modernize their economies, many countries are now looking to implement payment systems as part of their digital public infrastructure (DPI) approach. The World Bank reports that over 60 countries are working on building inclusive and secure DPI, focusing on digital IDs, government-to-person payment systems, and data-sharing frameworks. The “50-in-5” campaign led by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) aims to help 50 countries implement at least one DPI component within five years. As of now, 22 countries, including Estonia, Bangladesh, Singapore, and Sierra Leone, are actively participating in this effort to accelerate digital public transformation.

When core, horizontal DPI components like payment systems are implemented, they become the virtual “operating system” of a country as they get reused across every sector of the economy. Such systems can be used by verticals like financial services, healthcare, and logistics, as well as sectors including government, industry, and non-profits.

Digital Payments are also the fastest and most affordable path to financial inclusion. Since the cost of serving people through digital means is far lower than using physical touch-points like bank branches, investing in digital payment systems goes much further, and faster, in enabling financial inclusion.

India and Brazil are two countries that have done this successfully with the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and Pix respectively. The motivation for implementing DPI payment systems can include one or more of the factors listed below:

- Financial inclusion

- Reducing leakages in Direct Benefit Transfers

- Bringing people into the formal economy, thus improving tax collection

- Digital sovereignty

- Interoperability

- Reducing transaction costs

- Enabling innovation in payment systems

Yet, to fully understand the impact of DPI payment systems, metrics are needed.

As the famous management guru, Peter Drucker, said, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” DPI is a means to achieving policy objectives, and robust mechanisms are needed to measure its impact. And, because DPI is not merely an approach to technical infrastructure but also societal infrastructure, it is critical that countries continuously evaluate how DPI systems are contributing to their policy and societal goals.

Today, despite the critical importance of DPI payment systems, research into their impact is sporadic and insufficient. A large percentage of the research that exists takes an inside-out perspective, using data generated by the payment system to arrive at conclusions, rather than first determining which metrics might be needed to best understand and evaluate people’s experiences.

Largely, this is because, while some factors like digital sovereignty are easy to measure, others like financial inclusion are contextual and harder to measure. If an economy is resilient to the threat of external sanctions against domestic payment systems, it can be said to exert sovereignty in this domain. This can easily be determined by examining whether the payment networks are owned by domestic or foreign entities, and the extent of control that the central banks and government agencies are able to exert over these payment networks. On the other hand, financial inclusion is much harder to measure because it requires extensive field research and analysis. In countries where populations are geographically dispersed and speak multiple languages, such analysis becomes even more complex. Understanding who is excluded and why, and what motivates early adopters to embrace payment systems requires building trust with local communities and convening focus groups – and might involve extensive travel. This makes such research time-consuming and expensive. In countries with large population sizes and far-flung geographies, the costs could run into millions of dollars.

Discussions around DPI can swing from wildly optimistic to concerning worst-case scenarios. Good impact measurements can help ground these discussions in reality and enable stakeholders to have more nuanced discussions that help minimize the risks and amplify the benefits of DPI.

We’ve identified several key considerations for effective DPI impact measurement.

Countries implementing DPI should see themselves as custodians acting on behalf of their citizens and measure the impact of DPI payment systems against their stated policy goals.

As they go about building impact measurement systems, we recommend the following:

- Impact measurement should be a continuous, systematic process and not a one-off event.

- Measurement needs to go beyond measuring first order impacts (number of transactions, value of transactions, number of active accounts, etc.) to measuring second order impacts (number of new individuals and firms onboarded, increase in savings rates, customer satisfaction metrics like Net Promoter Scores, gender inclusion, access to credit & insurance products, improved resilience to financial shocks, etc.). A mix of qualitative and quantitative research methods should be used to measure impact.

- Subjective parameters like trust (which encompasses issues like privacy, cybersecurity and faith in the DPI ecosystem players) should also be measured and efforts should be made to continuously enhance trust.

- From a financial inclusion perspective, special efforts should be made to measure the impact on underserved sections of society. Bridging the gap between the well served and underserved sections of society should be part of the key performance indicators (KPIs) of DPI, and management should be measured on the delivery of these KPIs.

- Payment systems are built on top of multiple layers like identity, bank accounts, connectivity, and reliable access to power. Research can identify bottlenecks in the growth of DPI payment systems and suggest ways to remove them.

- Because robust primary research can be expensive and time consuming, DPI implementors should budget sufficiently for impact assessment research from the beginning. To further support these efforts, complementary research like The State of Aadhaar Report by ID Insight and Omidyar Network can provide added insights. In addition, raw data from these research efforts should also be made available as open data so that other researchers can examine it from multiple perspectives and suggest solutions.

- To create greater consistency among research efforts, there is an urgent need for investment in both a common reference framework for DPI measurement – one that creates a common taxonomy around outcomes and fills the current gap in specific impact indicators – and a model for scaling and sustaining such a measurement framework.

India’s story shows how effective research efforts can foster greater understanding around DPI’s impact.

For effective DPI measurement, primary field research is critical to examine the lived experience of users, and a mix of quantitative and qualitative research is needed to help policy makers fully understand the real-world impact of DPI systems.

India provides an interesting example of the importance of these differing research methods, particularly in relation to its Unified Payment Interface (UPI). Researchers across the World Economic Forum, Local Circles, Women’s World Banking, and the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) have produced key insights into the system and those who use it.

The World Economic Forum studied India’s Unified Payment System and found that as of February 2023, approximately $3.66 trillion has been transacted through UPI methods since its inception in April 2016. WEF estimated that this amount, if not transacted through UPI and transacted through cash, credit/debit cards, or other modes of payment, would have cost the economy approximately $67.07 billion to $87.80 billion. This highlights the impact of UPI on the Indian economy. WEF pointed out that, “despite the significant investments made in the development of digital public infrastructure in India, there is limited research on the impact of these initiatives.” Another study conducted by Local Circles found that 75% of UPI users said that they would drop off if fees were charged. This helps players in the UPI ecosystem understand the ground realities and plan their business strategies accordingly.

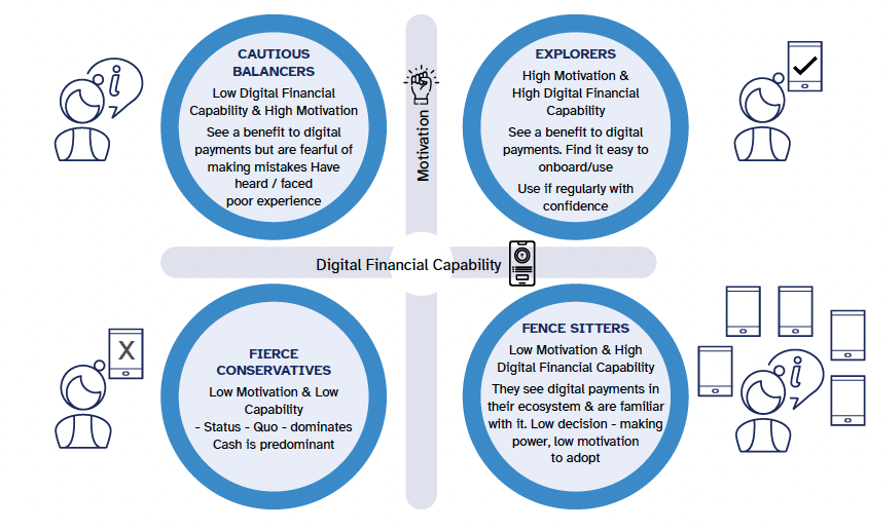

In addition, to understand how women use UPI, Women’s World Banking and the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) released a report titled, “UPI for Her.” The report identified women’s motivations and barriers to using UPI and provided a roadmap for financial service providers, fintech firms, and governments. The report identified four personas of digital adopters and outlined strategies for addressing each persona.

The study recommended that to maximize the impact of digital payments among women, it is essential to digitize wages, foster partnerships, promote financial literacy, and gather gender-disaggregated data.

This research found that women in the Cautious Balancers and Fence Sitters categories emerge with the highest potential in adopting UPI given their access to smartphones, awareness about UPI apps, and moderate usage of digital financial transactions. The report went on to say:

As they comprise a sizeable segment of the population, they could be the next wave of UPI adopters in India. Our on-ground examination revealed two simple ways to nudge them to become active UPI users: for the Cautious Balancers, a prepaid payment instrument (PPI) is the safest avenue for making inroads into digital payments; for the Fence Sitters who run micro-businesses, hand holding them into the realm of digital merchants tools and familiarizing them with the larger digital ecosystem for their entrepreneurship can lead them to fully embracing digital payments. (UPI for Her, p. 12)

These findings highlight the need to prioritize DPI as an approach to social infrastructure rather than merely technical.

As digital payment usage continues to grow, DPI impact metrics will remain critical in maximizing benefits.

Globally, billions of dollars are being poured into the development and deployment of DPI, yet very little is being invested in measuring the impact of these systems. Ultimately, this impacts the governance (or misgovernance) of DPI. Funders and DPI builders must urgently make impact measurement the cornerstone of DPI governance.

By establishing the necessary foundations, including a common reference framework, standardized research funding by DPI implementors, and systematic measurement expectations, the DPI community can better gauge and maximize DPI’s impact on individuals across the world. This is essential for ensuring that people – the “public” in “digital public infrastructure” – benefit from the billions of dollars being invested in developing and deploying DPI.