Digital transformation is not a new concept. Governments, companies, and non-profits have been digitizing for decades. However, in the past few years, a new term has popped up – digital public infrastructure (DPI). DPI is a specific approach to the design and deployment of foundational digital systems that, when done right, delivers impact beyond the sum of its parts.

And yet, like digital transformation, DPI is not automatically good. DPI must be intentionally designed, deployed and governed to maximize public value creation, following clear design principles and prioritizing the rights and aspirations of all people. For DPI to live up to its potential, therefore, it requires a strong ecosystem, or field, that is comprised of robust knowledge base, a diverse range of actors that share similar field-agenda, and sustainable and sufficient resources.

Such ecosystems evolve over many years – for example, the financial inclusion field emerged from the microfinance movement that started fifty years ago with the founding of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. To gain a sense of how mature the relatively young DPI field is, DIAL convened key actors in the DPI field through our Digital Donors Exchange (DDX) roundtable series. We’ve held two conversations on the state of DPI field building to-date, in January 2024 and January 2025. These two conversations leveraged a framework developed by Bridgespan to assess the maturity of the field.

To kick off the retrospective discussion, we invited guest speakers to offer their perspectives:

- Colin Colter, former Chair of the Atlantic Council working group on the Future of Digital Public Infrastructure

- Emmanuel Khisa, Africa Director, Center for Digital Public Infrastructure

- Diana Sang, Africa Director, Digital Impact Alliance

These five observable characteristics together unlock a field’s progress towards impact.

The two roundtable discussions relied on Bridgespan’s definition of a field, which is based on five characteristics. The discussions focused on the first four, as the fifth – adaptive infrastructure – emerges when the other four have reached maturity.

- Knowledge: The body of academic and practical research that helps actors better understand the issues at hand and identifies and analyzes shared barriers.

- Field-level agenda: The combination of approaches field actors will pursue to address barriers and develop solutions to the field’s focal problem or issues.

- Actors: The diverse set of individuals and organizations that together help the field develop a sense of shared identity and common vision.

- Resources: Sustainable and sufficient resources (financial and non-financial capital) support the field’s actors and infrastructure.

- Adaptive infrastructure: The connective tissue that enables greater innovation, collaboration, and improvement among a field’s actors over time.

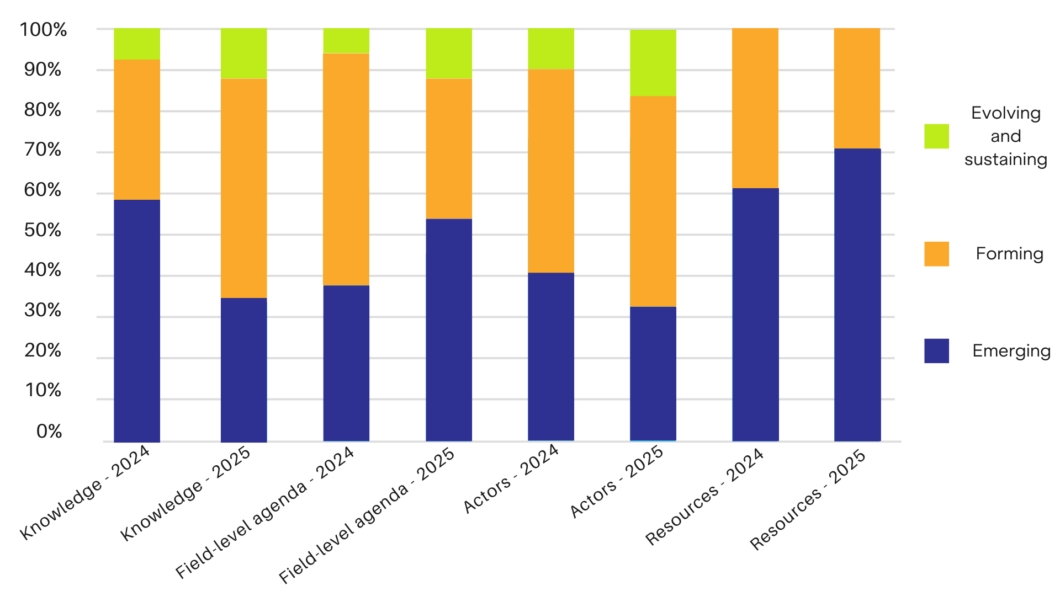

Each of the four characteristics were assessed across three stages of maturity: the emerging phase, forming phase, and the evolving and sustaining phase.

Polling data provides a snapshot of how perceptions of the state of the DPI field have evolved from 2024 to 2025.

The side-by-side comparison suggests that while our collective knowledge of DPI has increased alongside a maturing group of diverse and relevant actors, the sense that we have a shared field-level agenda has, in fact, decreased. Furthermore, the sense that we have secured sufficient and sustained resources has not increased, despite the creation of dedicated DPI teams within key donor organizations in 2024.

The discussion provided further insight into the group’s perception of the DPI field, uncovering key opportunities and gaps.

1. With the knowledge base growing, there is now a pressing need to establish clear metrics to measure the impact of DPI to show how, and if, it is helping people.

Amongst the group, there was a common belief that DPI is more than just the sum of its parts. But without a set of standard indicators for measuring DPI’s success, there is no way to illustrate this point. There was consensus among the group that the DPI field is lacking a shared understanding of standard indicators or a unified way to assess and understand the success of DPI initiatives.

What was on the participants’ wish list for metrics?

- Metrics that quantify DPI’s overall contribution to GDP, job growth, or new services to show how DPI is contributing to economic development by spurring private and public sector innovation;

- Metrics that illustrate non-financial benefits, including improved access to services and better quality of life.

The key opportunity to advance the knowledge base of the DPI field? A common reference framework to bridge key measurement gaps. Read our call to action.

2. To advance the field-level agenda, DPI efforts need to be treated as a driver of economic social progress – not as technology initiatives.

When reflecting on why DPI does not always, in reality, feel like more than a sum of its parts, participants noted the DPI is sometimes treated separate from national digital transformation strategies, rather than as a foundational layer. This allows DPI to be siloed within ICT or digital ministries, limiting cross-sector collaboration, risking duplication, and undermining DPI design principles including interoperability.

The group recognized that donors contribute to this fragmentation by choosing to work with different ministries, focusing on sectoral solutions, and failing to de-duplicate funding streams.

The key opportunity to advance the field-level agenda? Participants imagined ways for governments – rather than international actors – to take ownership of DPI efforts. Perhaps, DPI leadership within governments could be driven by a designated and nimble DPI unit that coordinates efforts across ministries. For more on driving intragovernmental coordination to advance digital transformation, read our insights from Sierra Leone.

3. To further mature the diversity of relevant actors, the DPI field needs clearer models for public-private collaboration.

There is no universal model for DPI – which is core to its strength as an approach. Countries can mix, match, and adapt technologies and frameworks to develop a customized approach for their needs and context. However, this means that countries can sometimes struggle to determine which approach will work best.

During the discussion, participants mentioned several questions that arise, including:

- Should DPI components be state-led, public-private, or market-driven? What are the benefits and risks of each in terms of maximizing public benefit, and how does the governance shift depending on the model?

- How do governments manage procurement and vendor selection in areas where there is limited competition (i.e. digital ID)?

- How should governments balance the benefits of global services, particularly cloud services, with the national priority to retain data sovereignty?

The key opportunity to ensure that the DPI field includes the right set of actors? The discussion points to the need to create clear models for public-private partnerships in DPI, as both sectors are needed to design and deploy DPI that works for people, regardless of the specific country or approach. This can be advanced through efforts to bring together public, private, and civil society actors, such as the Africa Data Leadership Initiative (ADLI).

4. Securing sufficient and sustainable resources for DPI requires strengthening local financing mechanisms.

Participants acknowledged that we have not yet unlocked enough funding models to allow DPI to sustain itself organically. Many DPI initiatives currently rely on external funding, depending on donor support rather than domestic budgets. Donor funding is increasingly unsustainable, and is often designed to meet donor, rather than country, priorities. Private sector funding is another possibility, but participants again noted questions around the role of the private sector. In this case, private sector financing may risk making DPI profit-maximizing, at the cost of public benefits.

Thus, there is a need to secure funding for the on-going costs of maintaining DPI systems and related institutions through national budgets. If securing sustainable domestic funding means raising taxes or adding fees to services, participants also discussed how to balance this with any negative impact on usage. For example, some countries charge fees to companies and institutions that benefit from ID authentication services, while keeping these services free to individuals.

The key opportunity to secure sufficient and sustainable resources? The discussion identified two opportunities here. First, lower costs by sharing, improving, and reusing digital systems, as per the Principles for Digital Development. Second, help governments better understand the long-term cost of DPI – including technology, institutions, and other governance mechanisms. Learn more about the non-technology costs of DPI.

Further maturing the DPI field is critical to sustaining DPI that maximizes public benefit and advances all sectors – regardless of shifting global priorities.

DPI, as with all digital transformation, is a horizontal investment. In other words, it can benefit all sectors by improving service delivery and creating the rails for innovation that can address challenges that communities face across job markets, health, climate, agriculture, education, etc. Furthermore, DPI is critical to advancing priorities such as inclusive AI and data privacy. By strengthening the DPI field, we are creating a solid ecosystem that can sustain this critical and cross-cutting foundational layer for the long-term.

How do you think we can advance the DPI field this year?