Throughout Summer 2022, the Digital Impact Alliance (DIAL) held a series of consultations in partnership with the Digital Public Goods Alliance (DPGA) and other partners to inform the scope and substance of the Digital Public Goods (DPG) Charter.

Throughout Summer 2022, the Digital Impact Alliance (DIAL) held a series of consultations in partnership with the Digital Public Goods Alliance (DPGA) and other partners to inform the scope and substance of the Digital Public Goods (DPG) Charter. Read the introductory blog of this series here for more background and context.

Key Insights

1. Sustaining digital public goods is often challenging due to issues in receiving money and using community resources for maintenance and improvements to the code.

2. Software communities are key to maintaining and improving digital public goods, but their decentralized nature makes coordinated governance and resource allocation especially difficult.

Background

By nature of being open-source, digital public goods promote sharing between countries, thereby lowering implementation costs, allowing for customization to local needs, and nurturing a local digital workforce.

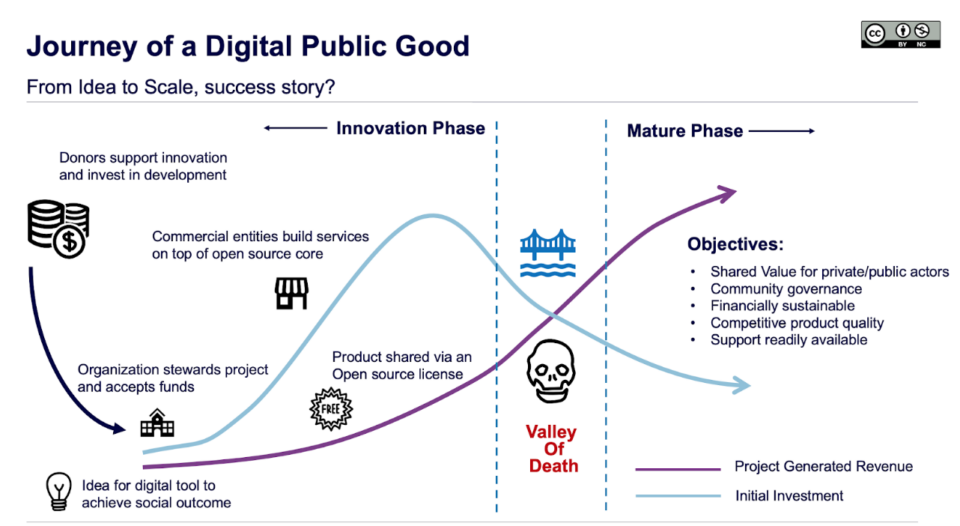

Our recent consultation process uncovered a critical barrier though: Despite strong demand for digital public goods these products collectively struggle with long term financial sustainability, beyond receiving initial donor investments. Monetary contributions to implementations of digital public goods do not always flow back to support the core product, and coordinating non-monetary contributions from software communities can be challenging.

For this reason, the DPG Charter will mobilize commitments to develop a diverse set of discoverable, sustainably-financed, effectively-managed, and interoperable digital public goods, supported by strong community contributions and qualified vendors that can implement them as digital public infrastructure in countries. This is one of five outcomes in the vision to build out safe, inclusive, and open digital public infrastructure for all.

We developed the following two key insights on Products through consultations with product owners, system integrators, and global policymakers, in order to figure out how digital public goods can be supported over the long-term for implementation in countries.

———

Insight #1: Sustaining digital public goods is often challenging due to issues in receiving money and using community resources for maintenance and improvements to the code.

Digital public goods frequently struggle over their lifetimes to receive money and use community resources for maintenance and value-addition of the “core,” or the code at the center of the product.

While there are many revenue models for digital public goods, the nature of decentralized communities around open-source software creates a “free-rider problem,” whereby not all community members are incentivized to contribute back to the core product and create value on top of it. This free-rider problem is exacerbated with digital public goods because of the imperative to design these products and package them for use by sovereign entities.

The distributed and independent nature of autonomous actors working on digital public goods — with no obligation to contribute back to supporting its core — limits their ability to become sustainable without subsidy from donors or legal, fiscal homes. One of the main expressed needs from our consultations was for products to find new money and resources towards recurring maintenance of the core, given the nature of the free-rider problem.

This is easier said than done, because creating sustainable digital public goods is hard. Not only given the free-rider problem, but also because their overall cost for financial sustainability of digital public goods is often higher than estimated. While many digital public goods’ communities receive income primarily from donors, grants and membership, others (like Primero) are exploring different ways of providing services and sustaining their products.

Product owners expressed acute needs in the following three key areas: development costs, non-development costs, and operational costs.

- Development costs: Product owners reported that funding is needed to cover consistent staffing — estimated at the cost of three to four technical staff (developers, development/operations, and/or project management) working with a developer community — before a product can even be deployed. This is compounded by the need to compete for qualified staff with well-financed private companies.

- Non-development costs: Product owners need funding to cover expenses related to the capacity-building and implementation of their products, as well as for engagement with the broader community. This can include (but is not limited to): developing and implementing training programs, documentation of products and codebases, education and awareness initiatives, events, travel, and miscellaneous operational expenses.

- Operational costs: Product owners need more support to “keep the lights on” on an ongoing basis. This includes money to cover ongoing operational costs such as human resources, logistics, hosting, and other recurring costs. That said, there is not a one-size-fits-all model for doing this, and new ideas like a foundation to provide common services (discussed later) are continually being discussed.

As a result of these difficulties, product owners highlighted during the consultations how they must constantly look for alternative sources of funding and capital to keep a product going, diverting human resources away from the product itself. This leads to many digital public goods becoming reliant on donors to subsidize their products’ growth and continued development.

Commercial business models like software-as-a-service (SaaS) are not usually an ideal fit for digital public goods (or in some cases not possible, depending on the organization’s legal status). In particular, service fees alone are often insufficient, as these products must offer competitive price points for governments and other implementers. Product owners are continuing to experiment with new business models, but there is a dearth of best practices in this area. Fortunately, many expressed optimism that this can be improved in the coming years.

Going forward, donors and others will need to better acknowledge the true costs of supporting digital public goods as they make investments, such that they can divert their efforts to improve the sustainability of those products. We believe that it’s not too late to break the cycle. Here are three practical ideas suggested by our consultations:

- Move towards more holistic views of how governments use and sustain open infrastructures. Such a view would emphasize persistent monitoring and feedback over a project’s entire lifecycle, to help break feedback loops that lead to an over-emphasis on deployments rather than long-term maintenance.

- Brainstorm ways to drive organizational and behavior change. Examples include moving away from single grants limited to deployment costs only towards value capture that can support the core business over time.

- Explore alternative financing models include pooled procurement, three-sided marketplaces, joint funds, and others to correct some of these market failures. A key priority in the near future will be documenting the effectiveness of these different models.

While these lessons are generally applicable, the relevance may vary product-to-product depending on those products’ size and governance models. Ultimately, models for the business sustainability of digital public goods should address these different realities.

———

Insight #2: Software communities are key to maintaining and improving digital public goods, but their decentralized nature makes coordinated governance and resource allocation especially difficult.

Digital public goods often rely on open-source software communities to create value through technical and code contributions, in addition to thought leadership, in-kind support, awareness-raising, and capacity-building. That said, best practices for governing digital public goods and engaging the software communities that make them possible remain a matter of some debate.

Digital public goods product owners struggle to balance the benefits of community engagement, which is critical for improving open-source codebases, with the time and resource demands of engaging with and leveraging these communities. This is because as open-source projects are opened up to the community, coordinating the flow of money, time, and resources to support the core can become more challenging.

How digital public goods are engaging with software communities depends largely on how they are governed. There are many archetypes for governing digital public goods but generally speaking, two models are most prevalent: single-vendor governance and community governance.

“Now’s the time to collaborate and build inclusive digital public infrastructure with the primary goal of improving the lives and livelihoods of all.”

Michala Mackay, Chief Operating Officer; Director Sierra Leone Directorate of Science Technology and Innovation

These two models distinguish between highly centralized approaches (single-vendor, which tend to be more vertically-integrated) versus more decentralized approaches (community governed, which tend to be more horizontally-integrated). However, few fit neatly into one approach or another. Single-vendors often pursue commercial revenue streams and can be a for-profit or non-profit, while community-governed models will require a central coordinating entity such as a foundation.

During the consultations, it was clear that this tension manifests itself in both the coordination and quality of software communities.

- Coordination: There is an open question as to which types of coordination work best for different types of open-source products, largely depending on the governance models highlighted previously. The more traditional approach to governing open-source products is to use a decentralized approach that relies on a network of freelancers, staff, and volunteers. Recent experience suggests that some products — such as those that underpin digital public infrastructure — should consider a more centralized approach to actively curate community contributions (if they accept them at all), but more evidence is needed as to how affordable and sustainable those models are.

- Quality: While the nature of open-source products creates an imperative to work with the community, the process of engaging with them and reviewing community contributions can be challenging. Depending on the type of products, it can sometimes take time away from developers simply making changes to the core themselves. This can undermine product quality and impact long-term performance. Product owners must, depending on how they are governed, be mindful of the value and impact of using community contributions and engaging with those communities to ensure the continuity of those products and their codebases.

The consultations suggested that the following ideas can help set a clearer approach for how to engage the community:

- Monitor and learn from the experience of many open-source products currently implemented at the infrastructure level, including MOSIP, Primero, X-Road, Mojaloop, OpenCRVS, Mifos, and others. Learning from the different experiences of different types of products can help to understand how to balance the benefits and costs of community-driven contributions.

- Generate more nuanced evidence on both what governance models work, and how to best leverage their contributions, both financial and non-financial. Many have core teams of experts to support their products, with varying levels of community support and centralization, while others are more community-driven.

- Create a foundation or custodian-like structure, which could help coordinate common services not requiring domain expertise. A central coordinating body such as a foundation can play a role in facilitating contributions from the community, but those in the consultations collectively-agreed, there must remain a long term commitment by donors to financially support digital public goods. Common services could include human resources, recruiting, and payroll. Examples to follow could include the Linux Foundation and the Apache Foundation.

———

These insights and practical next steps are invaluable to catalyzing effective commitments through the DPG Charter, which imagines a world where everyone has access to education, health care, and the essential services they need not only to survive, but to thrive. Digital products, particularly those that are open-source and designed for the SDGs, can help us make that a reality, if we work together.

With immense gratitude to those who participated in the consultative process, we look forward to sharing more insights through this blog series with you in the weeks to come. Stay tuned!