In today’s digital world, technology touches everyone, with sectors like education, healthcare, and even agriculture relying heavily on digital tools and services. As its prevalence continues to grow, we are increasingly in need of a means through which to ensure technology is properly designed and implemented – along with measures to protect users from potential harms. In combination, digital public infrastructure and online dispute resolution can prove an important means of achieving this goal.

Digital public infrastructure (DPI) is a relatively new term, having gained international recognition in recent years for its potential to convey important benefits – ranging from faster public service delivery to financial inclusion, to greater gender equality. As an approach to designing interoperable, sustainable, foundational digital systems, DPI is composed of layers including digital ID, payments, and data exchange and beyond. When working together, this infrastructure can promote positive digital transformation, allowing people across the world to participate in and derive value from digital society. A few popular DPI examples are X-Road in Estonia, Singpass in Singapore, Unified Payments Interface in India, and PIX in Brazil.

By contrast, Online Dispute Resolution dates back to the 1990s when the rise of large scale, largely private digital platforms like EBay created demand for effective and efficient means of grievance redressal, in order to retain the trust of their users. Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) is a mechanism to resolve disputes through the use of electronic communications and other information and communication technology. It often uses alternate dispute resolution (ADR) tools such as negotiation, mediation and arbitration. Since the 1990s, ODR has spread at different rates and in different sectors around the world.The shutdown of physical channels for dispute resolution, such as courts during COVID-19, greatly accelerated the trend towards adoption of ODR practices in many places.

Today, the dominant active usage of ODR remains on large private platforms like Amazon and Alibaba. Recognizing its importance, tech giants have taken the process of dispute resolution within their own ecosystems to new levels of scale and efficiency. More recently, banking and finance giants in India have adapted this playbook and embraced ODR, albeit third party provided, for their customers.

However, the rise of DPI as an approach challenges the notion that ODR is only or mainly a privately offered service within particular ecosystems. At the very least, it encourages consideration of how ODR can improve access to digital justice, especially for the increasing numbers of people engaging in online activities as a result of DPI adoption and growth.

As the need for DPI safeguards is increasingly recognized, online dispute resolution can play an important role.

In the context of justice accessed through digital public infrastructure (DPI), online dispute resolution is a key aspect in protecting consumer interest and upholding safeguards. In India, for example, multiple building blocks like eSign for contracts and eKYC for authentication help create a robust infrastructure for online dispute resolution (ODR) innovations.

Recently, we’ve witnessed a rising emphasis on safeguards for DPI, arising from concerns that if abused by their operators, whether public or private, DPI can be the cause of large scale problems for digital societies, to the extent of incurring undue inconvenience and costs and undermining public trust in them.

The UN Special Envoy on Technology recently convened a process to define safeguards for DPI, culminating in the Universal DPI Safeguards Framework published on September 24th. In this framework, among the foundational principles for a safe and inclusive society, is the requirement to “Ensure effective remedy and redress.” This type of requirement is not new for digital systems. It is embedded in other frameworks, like the OECD’s 2022 guide to Good practice for public service design and delivery in the digital age.

What is new is the scale of the need. Today, DPI systems such as UPI in India and PIX in Brazil process as many as 100 million transactions per day–that’s on average 70,000 per minute. With such a huge scale of interactions, and only two examples, the need for efficient and effective dispute resolution grows daily. Overwhelmed court systems, or even ombuds systems, cannot handle the volume of issues currently arising – let alone in future.

This leads us to the first point of the relationship: effective DPI needs effective ODR.

What is online dispute resolution, and what is its relationship to DPI?

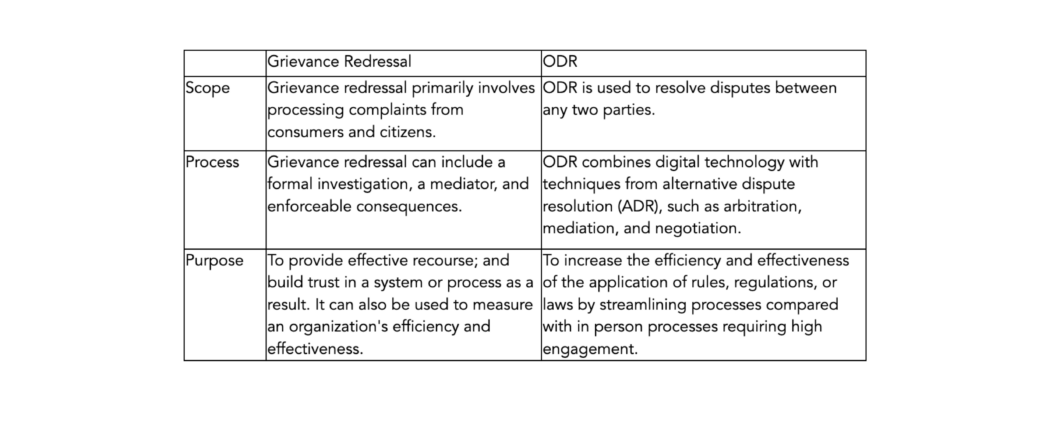

Broadly, online dispute resolution (ODR) refers to a range of mechanisms that resolve disputes through the use of electronic communications and other information and communication technology.

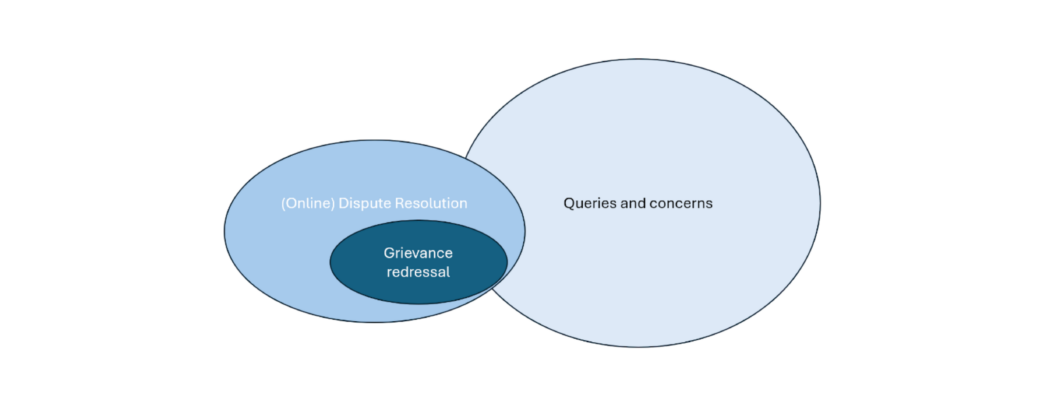

Grievance redressal, which can be carried out online and/or through physical channels, is one category of ODR that is particularly relevant in the context of DPI. DPI functions as large schemes–sets of institutional arrangements that define and bind the behavior of the participants (like payment providers in payment schemes) and operators of the schemes towards each other and towards end users or citizens. Grievance redressal is beneficial here, as it provides a process to address complaints or concerns users may have about the operation of the schemes according to their rules.

However, there are also forms of dispute which may not be grievances against the system or its operators, but which nonetheless have a material effect on how users experience the system. Some may escalate to become criminal charges against other users. For example, a rapidly growing category of digital fraud occurs through social engineering: criminal syndicates use digital platforms to deceive or coerce users into making payments or revealing their credentials. In the words of Indian research house Dvara, these transactions are authorized (in terms of system rules, so the user is usually liable for loss) but unintended. So, these are not narrowly grievances with the DPI system’s operation, but are unintended, yet real, side effects of large scale accessible digital platforms. Unless the DPI system can help to resolve it, user trust is quickly compromised.

To shed some light on this distinction, the following breakdown offers a way to understand grievance redressal vs. ODR more generally:

In addition, large digital systems must have the capability to handle large volumes of queries which can be addressed through providing appropriate information and may not be or become grievances or disputes. This framing is shown below, with the addition of the wider category of handling queries which may not be grievances or disputes but may lead to them if dispute avoidance is not practiced. We also need to keep in mind that ODR is being used for disputes generating outside digital systems like family disputes or criminal cases. This category is an essential interface, especially in environments of low digital literacy or with high proportions of recent adopters of digital channels.

Most DPI systems set some rules for how grievances are to be handled: for example, defining turnaround times or minimum availability of channels for complaint. Some regulators (as we will see in Part 2) even require that an online grievance channel be made available by participants in their customer interface to the DPI. Until recently, most DPI systems have not themselves had the digital infrastructure to support ODR functionality directly. That is now starting to change as operators of DPI consider the emerging needs.

This is where the DPI approach begins to return the favor to ODR – by thinking in a modular, interoperable manner, it is possible to contemplate how ODR can indeed scale to address societal needs. This leads to our second assertion about the relationship: ODR needs a DPI approach to be able to scale effectively to cover societal needs. Indeed, to go further, DPI offers an unparalleled environment in which to scaffold the development of ODR to new levels of coverage and effectiveness outside of, and even across, private digital ecosystems.

Moving forward, there are both opportunities and challenges to consider.

So far, we have postulated a two-way relationship between digital public infrastructure (DPI) and online dispute resolution (ODR): DPI requires ODR for effective grievance redressal at scale, and ODR requires a DPI approach to become embedded effectively.

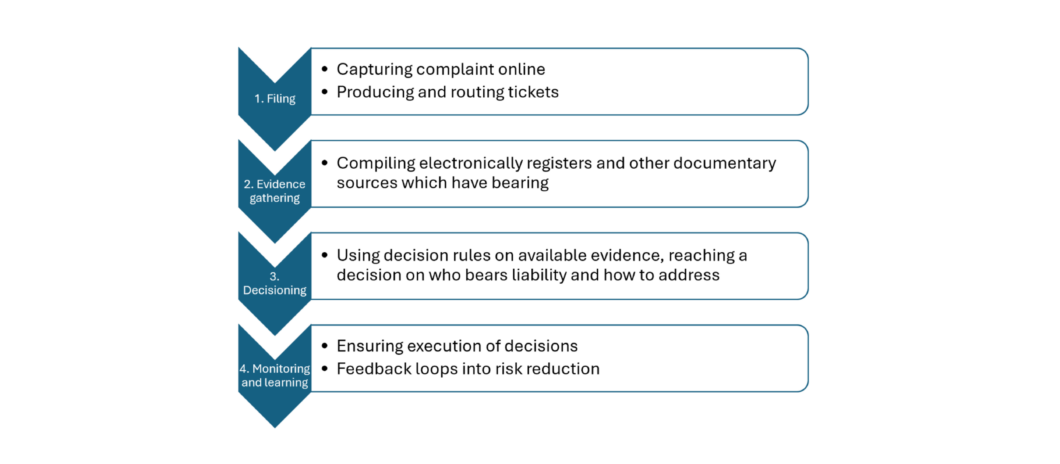

Yet, to date, the story around ODR in DPI has been mainly about the digitization of user complaint channels at the level of participants (think the banks in payment systems), rather than at the level of the system operator. However, the operator may also provide a channel for appeal if complaints are not resolved at the first level. This is the first step of an ODR process as shown below, and it is essential for managing the process thereafter.

The challenge and the opportunity for ODR in DPI is to extend beyond this first phase to incorporate evidence gathering and even decisioning. DPI systems collect data at large scale, which could and should enable the training of AI systems to reach fair decisions for a widening set of circumstances, while providing for ‘human in the loop’ recourse for undefined and unclear situations. This aspect could even be provided through creating a panel of independent arbitrators, which can be accessed easily in such cases, funded through levies or charges on participants. In theory, at least, this learning can be done better at the level of the DPI system – rather than at the level of individual participants who see only their part of the dispute chain, and which may extend across multiple participants.

As digital public infrastructure grows in popularity, online dispute resolution will grow in importance as a key safeguarding mechanism.

As countries across the world work to implement DPI, robust online dispute resolution will become increasingly important, as it is needed both to ensure users are fairly treated and to promote trust in the digital systems they use.

To promote a greater understanding of this two way relationship, the next expert opinion in this series will focus on emergent forms of ODR in DPI in India, outlining how these increasingly large scale systems provide learning for what needs to be done to shape that future.

This expert comment is the first of a three-part series on the relationship between DPI and ODR. In this first publication, we seek to understand what is the relationship between ODR and DPI and what it could be. In the second publication, we consider evidence from India, which is not only the home of leading DPI systems, but has an increasingly rich and active ODR environment across multiple sectors. We explore the question of why this has happened, and what the rest of the world can learn. And, in the final publication, we look at the possible agenda ahead for ODR in DPI, if the aim is to offer effective dispute resolution processes by design.

To learn more about our Digital Dialogues and our expert contributors, check out the webpage here.