Consent is a cornerstone of trust between users and the systems with which they interact. For digital public infrastructure (DPI), implementing consent mechanisms that are both meaningful and informed is crucial to maintaining this trust and ensuring that users have access to and can control the use of their personal data.

For example, simply clicking “I accept” on a webform requesting to transfer data to a third-party vendor, to enable getting to the next screen as quickly as possible, is unlikely to be sufficient to meet this bar. It requires transparency in how data is collected, used, and shared. People must be able to make informed decisions, with clear options for recourse if something goes wrong. This involves transparent communication, accessible terms, and mechanisms for redressal.

To better understand how this looks in practice, we use a technical lens to explore the different components – and considerations – needed to promote meaningful, informed consent within DPI.

Firstly, what constitutes meaningful, informed consent?

Meaningful, informed consent is the gold standard that systems should strive to support. In practice, consent is the result of overlapping efforts in the policy, technical, and legal areas.

Understanding what exactly consent is – and which elements comprise it – is critical in promoting a trusted digital ecosystem.

Let’s break it down.

Consent – aka. does the person give permission?

At its heart, consent is about the giving and receiving of permission. In the common vernacular, this is often in terms of providing permission for some type of action to be taken on the person by someone else. For example, consent forms are often signed before performing certain medical procedures.

In the case of digital systems, permission given by consent is more commonly referring to data about the person giving consent, often sensitive, personally identifiable information (PII). Herein, the permissions are for the processing and use of that data.

Meaningful – aka. is the person truly capable of giving permission?

To be meaningful, consent must be given voluntarily, by an individual who is capable of understanding the terms of the agreement. There are several different reasons why a person may be unable to meaningfully give consent.

One example is those who have not yet reached the age of majority. In most jurisdictions, minors are not able to enter into binding agreements. As such, consent provided by minors cannot be considered meaningful. This would also apply to those who are unable to enter into agreements under the law (e.g., in a guardianship or custodianship).

Another common example is that where a person is presented with a Hobson’s choice (e.g., accept this or your child will not receive the needed healthcare). In this, like other forms of coercion, the person has either limited or no freedom of real choice. Hence, there is no meaningful consent either. There may be legal reasons for why this circumstance may occur, especially when dealing with government services. However, “consent” provided under these circumstances would not be considered meaningful.

Informed – aka. does the person understand what permission is being given?

Informed consent occurs when the person providing the information understands several key aspects of the grant of permission:

- What information is being requested.

- What the information will be used for.

- Who will have access to the information.

- How long will the information be retained.

- What are the ramifications of providing that information.

Only with this information can the individual make an informed choice about whether they want to grant permission to use their information. In many cases, conveying the first four items in an understandable way can be quite difficult — the fifth even more so. Comprehension difficulties are increased with those with lower digital literacy and experience dealing with online interactions.

There are many key considerations when building consent mechanisms.

Consequently, meaningful, informed consent goes beyond mere formality. To carry out their intended purpose – allowing people to make key decisions around their information access – consent mechanisms must be thoughtfully designed. This includes taking into account factors like:

Transparency

This means users are fully aware of how their data is collected, used, and shared. For example, in a country’s national ID system, users should be informed not just about what data will be collected, but also how this data will be used across government services and if any third parties will access it. This information needs to be presented in a way that is simple and easy to understand. Technical and/or legal jargon must be avoided. Ideally, it should be presented in a language that is natively understood by the individual. Clear communication of these details builds trust.

Transparency extends beyond just the initial interaction where the consent is originally granted. Individuals need the ability to see who they are giving consent to – and for what purposes. They should also be able to see what requests have been made and granted to access their data. This is particularly important in data exchange systems that allow for legitimate access without full meaningful, informed consent provided for through legal mechanisms (e.g., some government processes and services).

Redressal

Sometimes things go wrong — even in the best designed systems with all the needed policy, regulatory, and enforcement support. There needs to be a mechanism by which issues can be identified and corrected.

These issues can take many forms, including unauthorized access, incorrect or out-of-date information, unauthorized usage, etc. While the consent systems need to have automation that monitor for such issues, providing a mechanism by which the individuals using the system can report issues, make complaints, and receive support is crucial. In the context of DPI, online dispute resolution can provide one means of effective grievance redressal.

For these mechanisms to be effective, they must be paired with institutional support and funding to allow for the requests for redressal to be acknowledged, researched, and addressed within a timely manner. This relies on policy, regulatory, and enforcement support from the government. Enforcement must be such that bad behavior (e.g., treating violation penalties as simply a fee for doing business) is effectively discouraged.

Types of consent

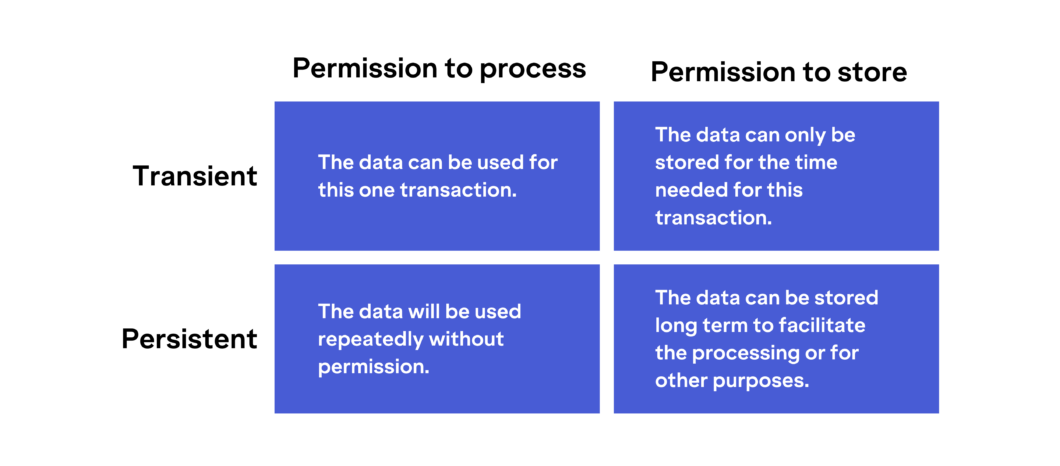

Within a digital transaction, consent can be given for several different types of data actions. This can affect how the data is used by the requestor. An example of this is the following simplified view:

Naturally, each of these scenarios will be affected by laws and regulations, such as data retention requirements for know your customer (KYC) or anti money laundering regulations for financial service providers.

Let’s look at how effective consent works in practice.

Consent is both a process and an agreement concerning four different entities:

- The individual to which the data relates (often called the subject).

- The individual who provides permission (often the subject, but not necessarily in cases like a parent of a minor child).

- The data requestor who is seeking to access the data.

- The data holder who has the requested data.

While this is the minimum number of entities, some consent processes add additional entities to facilitate the secure sharing of information (e.g., data mediators). These other entities can improve privacy, security, trust, etc., in the overall approach.

Like most parts of DPI, consent works in concert with the foundational technology layers. It forms a subprocess within a larger action and generally consists of the following stages:

- requesting consent from the individual;

- capturing and securely storing the individual’s consent decision; and

- enabling revocation.

Requesting consent

This is the initial step where individuals are asked for permission to collect, use, or share their data. The request must be specific, direct, and informative, allowing users to understand exactly what they are consenting to. For instance, a government portal may ask users for consent to share their health data with a healthcare provider, specifying how the data will be used, as well as the benefits and risks of sharing it.

When striving for informed consent, the request needs to be as clear as possible. This will need to consider the individual, their level of digital literacy, the physical circumstances in which the consent will be sought, the sensitivity level of the data being requested, local sensitivities, global best practices, and the context of the request. This can be particularly difficult to get right, and an iterative approach to continually refine and improve the process should be expected.

Even with these different considerations in place, it is important to recognize that a consent mechanism places additional requirements on individuals. As beneficial as it is, individuals are forced to now both consider and give/refuse consent. This creates both cognitive load and expenditure of time and resources. As previously mentioned, not all individuals may be able to easily take on this additional commitment. Another component affecting the level of commitment is the system design and the types/frequency of the needed consent.

Several approaches, such as fiduciary agents or smart (AI- or rules engine–based) agents, have been proposed. All of these add complexity, both in terms of legal and technological requirements, but also with consent itself. If the common or default path is handing consent decisions to a third party, how is meaningful, informed consent affected or is it even possible? We expect this to be an area of continued discussion as the right balance is sought.

It should be noted that because consent is just one component of an overall DPI approach, there are some assumptions about the rest of the process. For example, this stage assumes that all the entities involved in the consent process have already been determined. Otherwise, the consent request cannot be formed. It also assumes that there is a process external to the consent process to enact the actual delivery of the data. Other components, such as digital identity, are also assumed to have an enforceable agreement/grant of permission.

Capturing and securely storing the decision

Once consent is requested, the user’s decision — whether they agree or decline — needs to be accurately captured and recorded.

Subsequently, the consent information must be stored securely to protect it from unauthorized access or breaches. This stage ensures that there is a clear record of what the user has consented to, which can be referenced later if needed. This is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the consent process and safeguarding user trust. One approach to defining how the consent is captured and stored are consent receipts, which are designed with the processing of PII as the central focus.

A robust DPI approach would include encryption and other security measures to store this data safely, ensuring it cannot be tampered with or accessed by unauthorized parties. This security should extend to the content of the consent and the related metadata. An eye towards privacy (preferably following Privacy by Design principles) is essential.

Enabling revocation

As mentioned above, there are different types of consent. Revocation applies primarily to the circumstances where persistent permission has been granted. For example, it does not make sense to revoke permission to process age information for the purpose of purchasing an adult beverage six weeks after the fact. It would, however, make sense to potentially sever data sharing with a service provider when changing to a new provider.

Where applicable, individuals must have the ability to revoke their consent at any time, and the system should be able to process this revocation effectively. This means that if a user decides to withdraw their consent, the system should immediately stop using or sharing their data in the manner they had initially agreed to. For instance, if a user decides to revoke consent for a data-sharing agreement with a third-party service, the system should cease any further exchange of data with that service.

User portals and other tools should facilitate easy management of consent actions (e.g., granting, reviewing, and revoking) across digital infrastructure, as opposed to forcing individuals to understand and seek out consent occurrences across processes and workflows that may span multiple government agencies.

It should be mentioned that while future data-sharing can be stopped through technical means, stopping the future use of previously shared data cannot be enforced through technology. This is another area where policy, regulation, and enforcement need to work together to form a workable consent system.

Considering consent frameworks

Consent is a complex subject. Frameworks like ORGANS and GovStack provide structured guidelines for implementing each stage of the consent process. These frameworks help ensure that the consent mechanisms are consistent, secure, and interoperable across different systems, enabling a more seamless and trustworthy experience for users. For example, ORGANS might outline best practices for securely storing consent, while GovStack could offer modules for capturing and managing user consent in a standardized way.

With multiple approaches out there, governments should explore multiple consent frameworks to inform the strategy that will work best for their local context.

Informed, meaningful consent works best when integrated across the foundations of good DPI.

Consent forms an important part of a DPI approach, but it does not stand alone. Consent mechanisms must be designed to interact seamlessly with various components of DPI, such as ID systems and data exchange platforms. This ensures that consent given in one part of the system is respected across the entire digital infrastructure.

With consent only being part of the process that eventually results in the sharing of data, other DPI components and concerns directly interact with consent. Below is a non-exhaustive list of some of these.

Data exchange

When different systems need to share data, the consent system ensures that this sharing only happens if users have agreed to it. For example, if an individual’s health records need to be shared between hospitals, the system should check that they have given consent for this exchange.

However, permission to share the data is not sufficient in and of itself. The data will still need to be transported from where it currently is held to the data requestor. The data exchange, working with the consent system, is responsible for moving the data once proper consent is obtained.

Metadata and privacy preservation

When privacy is being discussed, there is often a focus on personally identifiable information (PII). As reasonable as this is, PII is not the only sensitive data that needs consideration. Metadata is often just as sensitive.

Metadata, like the time you logged in or the device you used, is often collected alongside your data. More importantly, metadata often records who you interacted with and at what time. An ideal consent system makes sure this information is handled in a way that protects your privacy, ensuring it is not misused or shared without approval. In other words, it treats the metadata just the same as it does PII.

Access / participation controls

Consent systems also control who can access an individual’s data. For example, an individual might choose to share their data with a particular service provider but not with others. The consent system ensures their choices are respected and that they can change their preferences at any time. Within the constraints previously discussed, this empowers the individual to manage who has access to their data and how it is used within the system.

These controls extend not only to the service side of the system, but also to the interface that is used by the individual. Both sides of the system need to be equally protected. This is improved by integration with the digital identity components of DPI.

Accessibility and inclusion

In a world that is not fully digital, digital consent systems are going to struggle to meet the needs of every individual. Local context matters. No single approach will suffice, and governments should plan for a multi-modal approach that takes into consideration diverse populations. While this will increase the complexity of the system, the alternative is to exclude and disenfranchise people.

It should also be noted that multi-modal approaches will increase the attack surface of the system, and special care should be taken to address the security considerations added by each mode and the resulting interactions between that mode and the rest of the infrastructure.

Some situations that come up in practice include:

- handling constraints on physical abilities (e.g., blindness)

- limited internet connectivity

- limited device availability/access

- low digital literacy

Some of these can be addressed through multi-modal technologies. Feature phones and smartcards might be used to deal with situations around limited access and connectivity. However, these will bring along their own concerns, such as increased risk of impersonation on a shared feature phone or loss of access through the loss of a physical card. Remediation plans should be put in place to deal with these concerns.

Other issues in this area are not purely technical. Consider the following illustrative story:

Tania is a traveling healthcare worker. She travels to different villages providing important services to those who live there.

Due to the number of villages that she needs to visit, she must make the most of every minute working with her patients. Time is of the essence, as it is important for her to visit with as many in the village as possible within the short timeframe she has with them.

A new government-supported program has introduced electronic record keeping, which should help provide better care management for the people over time, especially if they are displaced by a natural disaster or other upheaval. However, as part of this program, consent is needed for the villagers’ PII to be collected, processed, and stored in accordance with the country’s newly updated data protection laws.

Many of the people Tania is working with have low digital literacy, and many of these concepts are foreign to them. For Tania to explain these concepts to them to a point where the consent is both informed and meaningful will take time. Tania expects this to average about 10 minutes per patient. Over her visit, this extra time with each patient will have a direct, negative effect on the number of people she can see.

How can this dilemma be addressed?

There are some real tradeoffs that happen in this situation.

For consent mechanisms to be truly effective, policy, regulation, and enforcement are required.

Consent is not a technology-only problem. Any solution that purports to be able to solve it without the need for paired policy, regulation, and enforcement is overconfident in its techno-solutionist ability and should be avoided.

To be effective, consent mechanisms must be supported by robust policies and regulations that align with international standards. This ensures individual privacy is protected and that organizations are held accountable for how they handle consent and personal data.

Also, as referenced previously, data cannot be easily constrained. Once released, it becomes available with little to no technical oversight. This is where other types of oversight are needed.

Additionally, guardrails should be put in place to lessen the burden on individuals to fully understand the ramifications of the decisions being asked of them. Informed, meaningful consent is the ideal state. However, real-world situations will make this difficult (or even impossible) in some cases, such as when working with populations with low literacy and digital literacy. Policy, regulation, and enforcement need to fill in the gaps that this creates.

Without good policy, regulation, and enforcement paired with good technology, trust cannot be achieved.

Where to next?

With the unprecedented level of data collection that the modern digital era has brought, the question of who “owns” or otherwise controls the data about an individual has become a major area of discussion and disagreement. Over the last several years, there has been a growing consensus, driven in part by the incumbent use cases of medical and financial data and data protection legislations such as GDPR, that the proper place for this control is with the individual themselves. This conclusion necessitates the need for methods by which the individual can give permission or consent for this data to be processed and used.

Creating and executing a plan to build meaningful, informed consent is a crucial component of any DPI approach. Some meaningful steps that can and should be taken include:

- Recognizing that consent is multidisciplinary — Consent issues will not be solved by policy or technology alone. A robust approach is needed, and the plan needs to include efforts on the legislative, regulatory, technology, and enforcement fronts. In particular, the focus of enforcement is important, as without it trust in the entire system fails.

- Identifying disadvantaged populations — With any consent system, there are populations who may have a difficult time leveraging it. This could be due to infrastructure, literacy, digital literacy, age, or many other factors. These need to be identified and addressed as early in the process as possible.

- Undertaking community outreach and education — Putting in place meaningful, informed consent requires participation and trust. Consultations with community and civil society groups can help understand specific needs and address problems before they arise. Additionally, public education campaigns are important in helping individuals not only understand what the consent system is, but why it is important to them and how it affects their lives.

- Creating and supporting redressal systems — Things can and will go wrong. A strong redress process not only helps respond to issues but can also be a source of trust building, both in the consent mechanisms and in the wider DPI approach. This require resources, but the resulting benefits are worth the expenditure.