Governments deliver thousands of digital services, yet users often experience inconsistency, confusion, and friction. Simple tasks like filling out forms or applying for benefits can become frustrating due to a lack of standardization. To address this, governments have increasingly developed digital public infrastructure (DPI) to deliver better digital services through digital IDs, payments, and data exchange systems. However, clarity, consistency, and usability in user interfaces and experiences remain critical—and this is precisely where design systems fit.

What are design systems in the context of government?

For many people, a design system might seem like brand guidelines or UI Kits that live as a Figma library with color palettes, buttons, and simple instructions. These conceptions envision the “systems” part of design systems as simple groups of connected elements. In reality, design systems can get as complex as the needs of the system they operate within. In the government, design systems unify how public services look, feel, and function. This goes beyond visual consistency alone. By standardizing and streamlining the digital building blocks—everything from form fields to security warnings—governments can offer faster, clearer, and more user-friendly experiences. That means less time trying to understand a form, fewer errors when applying for benefits, and a more trustworthy impression overall.

Industry examples like Google’s Material Design and IBM’s Carbon Design System illustrate the scope and utility of well-developed design systems. Material Design provides not only consistent and intuitive interfaces across Google’s products but also detailed guidelines for gestures in digital devices and states of UI elements. Similarly, IBM’s Carbon Design System emphasizes uniformity and quality across enterprise services, incorporating standards of accessibility, and more recently, guidelines for products that incorporate AI.

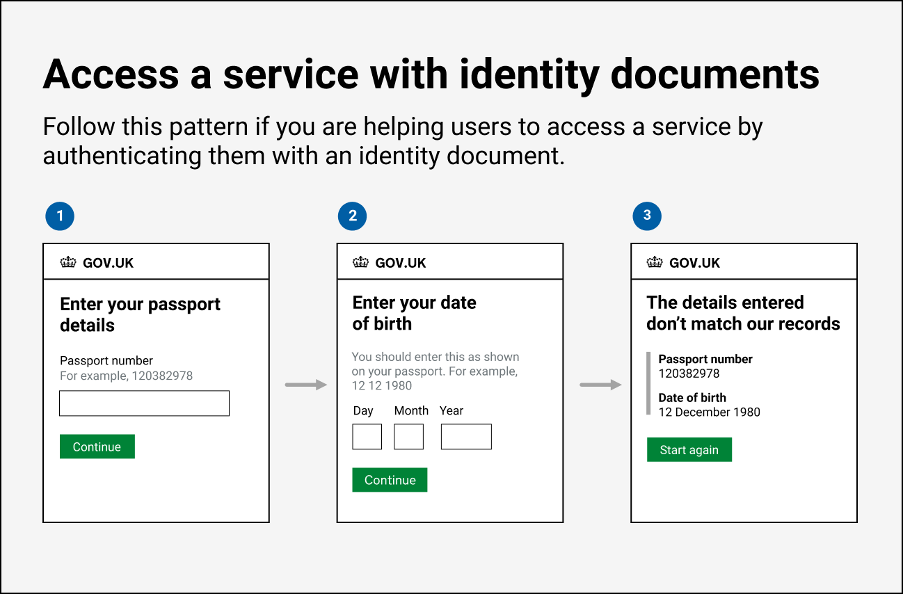

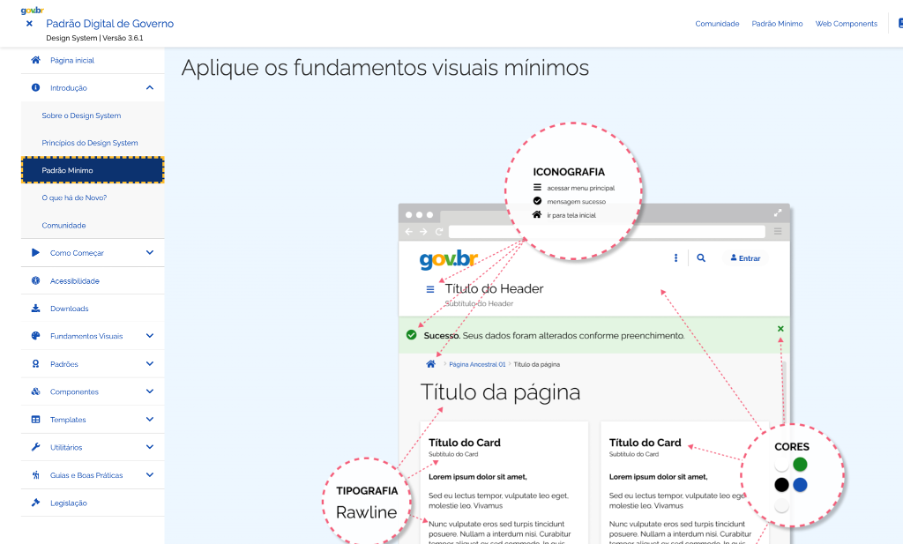

Not all governments are behind in this field. The GOV.UK design system, for example, is used by multiple teams in government to create consistent experiences not just for citizen-facing services (e.g. getting a driver’s license) but for professional services, such as lawyers (e.g. checking if a client is entitled to legal aid). The same system is the base for other design systems such as the Ministry of Justice, the Home Office, or local councils such as Hackney. In Brazil, the Padrao Digital de Governo is backed not just by guidelines, but by legislation and multi-department agreements and involvement, including Ministries of Economy, Social Communication, State Modernization, and more.

Design systems are more than visual consistency, but what makes them systemic?

Beyond visual consistency (all the government looks and feels coherent), design systems simplify actions using elements to scale public services with quality. They enhance our digital interactions with the state as citizens, entrepreneurs, or as civil servants.

This is done with patterns, components, styles, standards, and principles:

Patterns: Common forms of interaction with a digital system—such as creating or inputting passwords—ensuring best practices (security, memorability), technical requirements (character types), and troubleshooting (password resets).

Components: Elements used within patterns, like date inputs consistently formatted across services.

Styles: The visual identity of government sites (typography, colors, spacing, link presentation).

Standards: Compliance with guidelines for accessibility, privacy, and usability. The WCAG2 or the ISO 25010 are some examples that a design system can comply with. Also, the description of good practices are part of standards

Principles: More high level, they set the scene for all the elements of a design system. For example, a government can establish “Simplicity” as a principle, promoting straightforward information and less interactions, or perhaps “Be informative” which might entail explaining to the user what is required or how their info is processed using clear language. In the case of the Brazilian Government Design System: Unique experience, Efficiency and Clarity, Accessibility, Reuse, and Collaboration.

Elements in a design system are reusable (the same element can be used for different purposes) and modular (a set of elements can be used to build a bigger one). The sum of these parts and their consistent interactions transform a mere collection of elements into a coherent design system.

Design systems are important for citizens, businesses, and even the environment.

Design systems, as mentioned earlier, are not just to provide consistent interfaces, but to democratize all digital interactions with governments. In Mexico, my home country, we sometimes joke that you’ll get a great experience if you want to pay tax, but a terrible one if you need a tax return. Comparable/similar discrepancies can create frustration and erode trust. A well-crafted design system can tackle these uneven experiences by establishing a shared, flexible set of guidelines, components, and standards that every government service can use. Once adopted across agencies, citizens get a more predictable experience. A good design system allows functional consistency of the bureaucratic process: paying tax is as efficient as requesting a return.

Government design systems aren’t just for “citizen-facing” services. They also benefit internal processes and collaborations with private entities. Imagine a digital services company hired to modernize an online application portal for a specific department. If the government has a comprehensive design system—with a prototype kit and testing environment—then developers and designers don’t have to guess how forms or notifications should look. Everything from the color palette to the accessibility standards is already established, saving both sides time and money. As a result, projects get delivered faster, more consistently, and with fewer rounds of back-and-forth over design details. This same efficiency benefits companies when they need to use government portals themselves for things like licensing or tax compliance: they recognize common patterns, quickly find what they need, and complete it.

Although emergent, design systems are gaining attention in their relation to reducing carbon emissions, especially in government. The idea is that when interactions are standardized and intuitive, people spend less time clicking around or making repeated attempts to complete a transaction. This can lower bandwidth usage and reduce the overall computing resources required.

Can design systems be used as (or for) digital infrastructure?

A single common component may support services across the public sector, potentially at different levels of government. These components create public value well beyond the institution that operated them.

Richard Pope in Platformland: An anatomy of next-generation public services.

Design systems share many principles with digital public infrastructure (DPI): both provide interoperable, inclusive building blocks maintained at scale. DPI foundational components—like unified digital IDs, secure payment systems, or standardized data exchanges—serve as a technical backbone, enabling the design system to help people achieve foundational interactions with the state: make or receive payments, prove identity, and exchange information securely. By providing consistent and reliable methods for these essential interactions, DPI simplifies and standardizes complex backend processes. A design system enhances these foundational components by ensuring they are clear, intuitive, and accessible from a user perspective. Legibility is a pillar of digital interactions: if the backend of a government’s DPI is extremely secure, but difficult to use or hard to understand, scalability and adoption of DPI by the people it intends to serve is at stake. Design systems need DPI and vice versa.

GOV.UK Forms — a simple interface that civil servants can use to spin up forms — exemplifies this synergy. Because every field, button, and flow in GOV.UK Forms relies on the design system, the resulting services are consistent, accessible, and easy to maintain. Soon, this platform will allow civil servants to integrate authentication, payments, and secure data exchange into one streamlined form. That means a single journey—from proving your identity and paying a fee, to sharing information with the relevant department—can happen in one place, using the same coherent design elements throughout. If we consider the “shared means to many ends” principle, like well-maintained roads or a well-integrated public transport system, standard design components ensure everyone can navigate government services with minimal friction rather than bouncing among fragmented interfaces. Just imagine a highway or a metro with poor or no signs. The value of (digital) infrastructure lies in its use.

With DPI now enjoying momentum of political and financial support worldwide, design systems also need to be recognized as core digital infrastructure—funded, sustained, and treated as future-proof foundations. As more processes become automated and proactive (for instance, a system that renews your documents or calculates your benefits before you even ask), design will be at the center of how we experience and trust government services.