India is home to one of the most developed and innovative approaches to digital public infrastructure (DPI). Aadhaar, the country’s digital identity system, allows online authentication of almost the entire population to access a wide range of public and private services, while the national digital payments system, UPI, is used on average 500 million times per day to make small, instant payments. India is also leading the way in the fast-growing field of online dispute resolution (ODR), which is increasingly becoming available to everyday investors, bank customers, and even users of social media as a mechanism to resolve grievances online.

In our first expert comment, we argued that DPI needs ODR to build trust, and equally, that ODR needs a DPI approach to replicate and scale. In this expert comment, we take a closer look at the emerging experiences of ODR in India, exploring examples that integrate ODR and grievance redressal for effective grievance and dispute resolution. Together with a group of experts in ODR, DPI, and policy and research in digital development, we specifically ask the question: what are the learnings that other countries can take forward?

India has taken an innovation-led approach to integrating ODR within its DPI. Here’s what it looks like across sectors.

While the state of DPI in India has been well documented, especially during India’s G20 Presidency in 2023, there is little known – or captured – about their use of ODR systems. This is because, in part, ODR is a broad term covering a diversity of approaches and spanning multiple sectors. As such, there is no single up to date overview available. However, the ODR Handbook, published in 2021 by Agami and key partners, has helped spotlight several emerging solutions in a handful of sectors.

There is a diverse range of actors in the ODR space in India. Judicial institutions play a key role from the government’s side, setting up regulations like mediation and arbitration laws. Banking, finance, and insurance organizations as well as eCommerce players are current operators that use ODR solutions to resolve disputes between their clients (although ODR solutions could be used by any organization in any sector). Then, there are ODR providers, startups like Sama,Presolv 360, Cadre and CORD, that provide these services to the operators amongst others. These stakeholders make up the ODR ecosystem.

Today, ODR models are most prevalent in the financial sector.

The financial sector is considered a pioneer and enabler of ODR innovation. A significant milestone came when ICICI Bank, a major banking group, challenged ODR firms to resolve a sample of credit default cases using ODR systems, instead of relying exclusively on the traditional judicial system. In 2019, ICICI awarded the winning firm a contract of 10,000 disputes to jumpstart the evolution of its solution. Since then, over 100 firms in the Banking, Financial Sector, and Insurance space have adopted some form of ODR or grievance redressal.

Below are a few examples from the sector that showcase key ODR initiatives. These initiatives have adopted a DPI approach, laying the groundwork for stakeholders to use the infrastructure for dispute resolution.

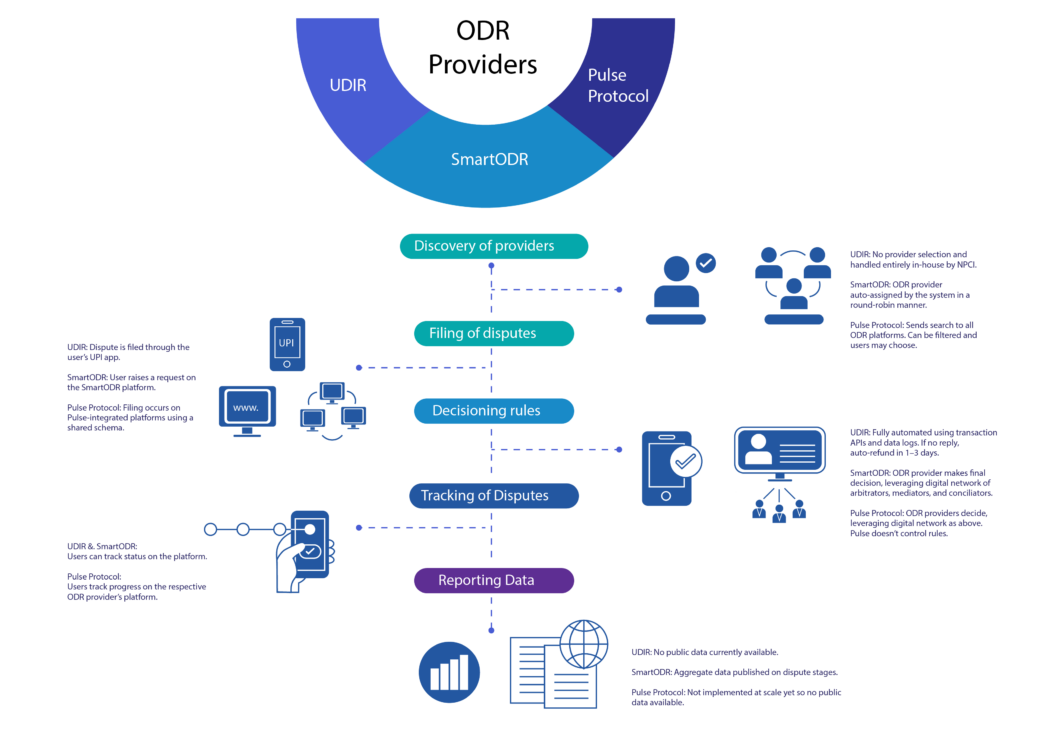

Unified Dispute and Issue Resolution by NPCI

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which regulates payments, and National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), which runs the country’s digital payments infrastructure including the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), have both taken active steps to set up an in-app grievance redressal mechanism and build an ecosystem for ODR in the financial sector. NPCI houses the Unified Dispute and Issue Resolution (UDIR), which is a comprehensive framework to tackle the complexities involved in resolving grievances and disputes within the realm of UPI payments. It is an automated, single-channel redressal system that looks to resolve issues with digital payments via UPI quickly and efficiently.

SmartODR by SEBI

In 2023, the financial securities regulator, SEBI, created the SmartODR system in addition to the SCORES grievance management system which has been operating since 2011. SCORES applies across seven major financial market infrastructures and makes it easier for investors to file and resolve disputes related to the securities market. The use of Smart ODR in 2023 offered investors access to independent ODR service providers – specialized firms – that were independently empanelled by the Market Infrastructure Institutions (MII) like stock exchanges. Since its launch in August 2023, investors have filed 8,485 disputes, of which a majority (5,553) used the ODR process, and of which almost two thirds have been resolved.

Account aggregators

Similarly, Sahamati, the industry association promoting open finance through account aggregators, has also adopted an approach to dispute resolution among its members through drawing on a panel of ODR firms assigned on a rotating basis.

ODR models are starting to emerge in other sectors.

While the financial sector has shaped the thinking of how other sectors implement ODR, the government’s aspiration is to apply ODR across multiple sectors. NITI Ayog, India’s apex public policy think tank, developed a plan for the use of ODR across government and engaging private players. While all the initiatives listed in the plan are not yet as mature as the financial sector use cases, they signal strong government intent.

Sectoral agencies have also incorporated ODR in their policies. For example, the draft National e-Commerce Policy proposes the use of an electronic grievance redressal system, including dissemination of compensation electronically for disputes arising from e-commerce. The Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) initiative published their Issue and Grievance Management, and ODR framework for resolving grievances and disputes between buyers and sellers in their network. They mention in the framework, that while this is the first step, the goal is to make this applicable to disputes between other network participants like the delivery partners or other discovery apps.

Other government agencies have gone further than policy alone. For example, the Grievance Appellate Committee was set up under the Information Technology Rules 2021 to handle online appeals from users aggrieved by decisions of social media companies and other digital intermediaries, specifically regarding complaints about violating their rules. As of August 2024, the Committee had received 1,332 appeals and addressed 1,278.

While government agencies are moving to adopt the ODR approach, others have sought to make it easier to access ODR as a legal service by adapting the Beckn Protocol. Beckn has been developed by FIDE and aims to decentralize economic transactions by allowing network nodes to search and procure different types of goods and services. The Protocol has so far been deployed to support ride hailing in certain places, power the Open Network for Digital Commerce, and, most recently, adapted to support decentralized forms of ODR as a service.

Pulse Protocol powered by Beckn

This approach is different from the others, as it takes a techno-policy approach rather than a policy-based approach only. PULSE, the Protocol for Unified Legal Services, adapts the Beckn Protocol to unify and simplify access to legal services. It works as a universal open language that facilitates seamless communication between platforms and legal service providers. A nascent collective initiative of members of the ODR service provider community and enabled by Agami and FIDE (the creators of the Beckn protocol), PULSE enables organizations to quickly integrate a range of dispute resolution and legal advisory solutions provided by ODR providers for customers and users. The protocol can be leveraged for any ecosystem, institution, and even for individuals seeking legal services to easily discover and engage with multiple legal service providers. Although a protocol itself is not considered DPI, the approach’s integrations could serve to foster efficiencies across systems that are in fact considered DPI.

While these initiatives have all integrated ODR, there are many similarities and differences in their approach to doing so.

One way to understand the similarities and differences across ODR initiatives is through the lens of the key ODR process stages, including discovery of providers, filing of disputes, decisioning rules, and tracking and reporting. Let’s examine the three initiatives listed above to gain a better understanding. We’ve selected these initiatives to showcase different approaches to ODR.

So, what can we learn from India’s experience?

India’s efforts to build an emerging ODR ecosystem using a DPI approach offer valuable lessons. In particular, we observe four key insights that countries could take forward.

1. Legal and policy backing by key federal institutions supported adoption and scale of ODR.

There is more confidence in sectoral stakeholders when the resolution and conciliation processes are legally binding. India has an existing arbitration law, the Mediation Act 2023, and has signed the Singapore mediation convention that promotes cross-border mediation settlements. These regulations give adequate foundation for ODR based innovations and scale. Hence, for ODR to scale across sectors, a directional framework from the judiciary and policymakers is critical.

In addition to attention from policymakers and planning agencies like NITI Aayog, the Indian senior judiciary has recognized and recommended digital technology as an enabler to improve the dispute resolution process. This instilled confidence in lower courts and sectoral ecosystems and provided the legitimacy it needed. During the pandemic, judges across court systems endorsed ODR as a required solution.

2. Curating spaces for select diverse stakeholders to understand all aspects of ODR nurtured a culture of innovation.

The India experience shows that ODR needs a diverse ecosystem of users, providers, regulators, lawyers, and judges to align on a set of broader rules and processes. The judiciary needs to understand the role of technology in the dispute resolution process to create the umbrella directional framework within which innovators can develop solutions for particular use cases scoped by sectoral entities. Without these stakeholders working together, the ecosystem will be stunted.

Agami played an important role as a catalyst in the emerging ecosystem in India by convening policymakers, regulators, market actors and innovators to focus on common use cases and highlight solutions. This is an important use of ‘curatorial capital’, a form of social capital which helps build active ecosystems. Agami then also played a role in advocating for adoption of ODR in DPI, greater interoperability of ODR solutions, as manifested in the nascent PULSE protocol initiative. This has fueled an innovation-led ecosystem which is responsive to different needs.

3. A general appetite for digital transformation within the government and wider society drove faster adoption of ODR.

For innovation to move beyond private-only spaces (in which ODR has been active before), it helps to have a generally aligned understanding and agreement about how an interoperable modular system can work for public benefit.

This is where India’s emerging DPI approach has infused and galvanized conversations about how to provide scalable tech solutions in the public interest, which have features like modularity and interoperability. This context has enabled a much wider conversation about ODR than if it were left to lawyers and enthusiasts only. Active engagement from civil society organizations to test and suggest valuable improvements to ODR providers can also be owed to a general knowhow and appetite to see technology as a tool to address developmental issues. Organizations like Dvara Research have been testing and suggesting improvements to ODR processes in digital payment systems like UPI to make it accessible to the wider society.

Furthermore, the fact that India’s public sector ODR transformation enjoyed successes first in the financial sector is not unique to India. The Cambridge SupTech Lab and implementing partners are actively experimenting in other countries with scaling the success of suptech software for financial authorities’ complaints handling, analysis, and dispute resolution to meet ODR needs of peer public sector agencies at national scale via govtech and ultimately DPI.

4. Experimenting with business models enabled diverse partnerships and deployment modalities.

ODR brings together different stakeholders of a value chain. Understanding the incentives for each of them will create faster buy in and engagement in the process. Innovative business models can play a catalytic role in this regard. There is also a lot of value in integrating grievance redressal and online dispute resolution processes. There have been different approaches to business models across the cited DPI examples above. While Sahamati has empaneled a set of ODR providers that participants can engage with in an online format, SmartODR encourages each market infrastructure institution (such as stock exchanges) to partner individually with as many ODR institutions as they need, depending on their caseloads. ODR providers also tailor their services to the institutions depending on the volume of transactions. There are multiple ways through which they generate revenues by a certain volume of transactions, or sometimes by white labeling or licensing their products. This experimentation with business models has led to innovation in the ODR space in India.

As a global leader in ODR, India provides valuable lessons, but there is still progress to be made.

The increasing use of ODR in India illustrates the two-way street set out in the first expert comment in this series: DPI needs ODR in some form to achieve scale, and ODR benefits from the DPI approach.

In many ways, India’s DPI approach has become a model and source of inspiration for other countries. So far, twenty-two countries around the world have signed onto the 50 in 5 Campaign, committing to implement national DPI solutions, indicating growing global interest in the DPI approach. If India’s experience provides any markers, it suggests that this trend is likely to drive the development of ODR systems in these countries in the years to come.

However, for all its emerging breadth and speed, India still has a long way to go to reach the goal of providing effective ‘digital justice’ for all. The established culture of innovation around ODR in the context of fast developing DPI in India will likely continue to provide useful lessons for extending ODR to other use cases and sectors and, ultimately, achieving population scale.

ODR and DPI

This expert comment is the second of a three-part series on the relationship between DPI and ODR. In the first publication, we sought to understand what the relationship between ODR and DPI is – and what it could be. In our second publication, we’ve considered evidence from India, which is not only the home of leading DPI systems, but has an increasingly rich and active ODR environment across multiple sectors. We explore the question of why this has happened, and what the rest of the world can learn. And, in the final publication, we will look at the possible agenda ahead for ODR in DPI, if the aim is to offer effective dispute resolution processes by design.

To learn more about our Digital Dialogues and our expert contributors, check out the webpage here.