Every day, scores of women navigate Accra’s bustling marketplaces in the hopes of making enough money to provide for their families. They sell vegetables, collect plastic for recycling, and work as tricycle drivers. On a good day, they manage to make around $3 USD; barely enough to scrape by. These women are the foundation of Ghana’s unofficial (informal) economy.

In recent years, Ghana has faced several economic crises, including rising inflation and a decreasing growth rate. As part of its effort to improve the overall economy, the government set an ambitious agenda for digital transformation, focusing on digitizing the country’s processes and essential services. While digitization can help drive growth and opportunity, we also see that, globally, the unique needs of women are rarely fully considered within digital transformation efforts – especially people working in the informal economy.

With that in mind, we sat down with Mary, Vida A, Abigail, Vida Q, Deborah, Vida T, Patience, and Charity*, along with several other women who work in Accra’s marketplaces. We wanted to hear about their experiences and learn how Ghana’s digital transformation efforts are shaping their lives and livelihoods. These conversations are one way that we hope, collectively, will help to more meaningfully understand how data and digital technology are impacting people and communities across Africa.

As the women explained, digital transformation has created numerous benefits – from a sense of belonging to economic opportunity.

In 2017, the Government of Ghana launched the “GhanaCard,” an official ID document issued to Ghanaians and permanent resident foreign nationals for the purpose of verifying individuals’ unique identity.

For Deborah and Patience, at its core, the GhanaCard affirms their identity as Ghanaians, a declaration of belonging. “It makes you believe and know that you are from Ghana,” said Deborah, in a statement of national pride.

But, the GhanaCard is much more than just an ID.

It’s a gateway that connects the women we spoke with to essential services, such as modern banking and mobile money. As they expressed, the ability to engage in digital transactions isn’t just a convenience, but a critical step towards their financial empowerment and security.

With the GhanaCard in hand, Mary and her peers can save, invest, and even build a safe financial future for their families by gaining access to official banking and mobile money services. Mary can also conduct transactions easily and securely, enabling her to participate in the growing mobile money industry and further her entrepreneurial endeavours.

“With the GhanaCard, I can finally open a bank account,” she explained. “It gives me access to banking and mobile money services.”

And, for women like Charity, a seamstress with dreams of expanding her business, digital payments offer a path to reach a broader market. The ease of mobile money can enable her to transact beyond the confines of her local community, tapping into a wider customer base and securing her income more reliably.

Yet, while these benefits are substantial, the women we talked to also experienced significant challenges.

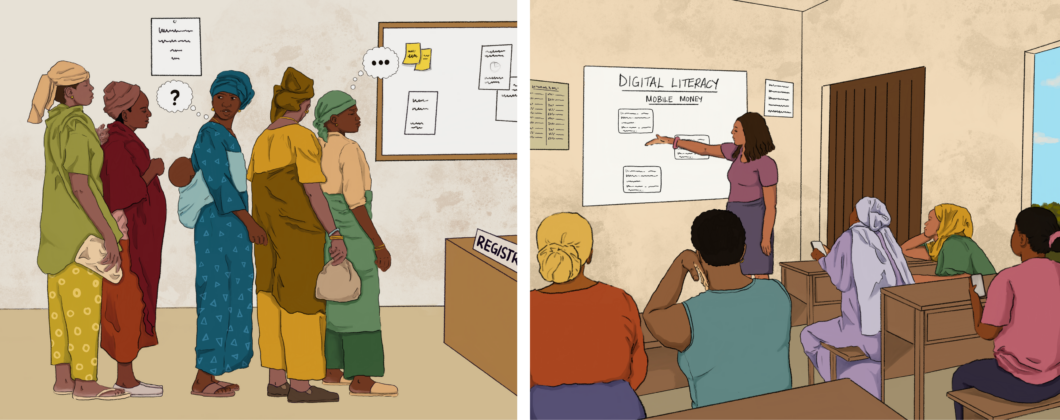

When discussing the obstacles of digitization, first and foremost, the women raised a lack of accessibility. For many, the registration process for the GhanaCard – mandatory for registering SIM cards and accessing mobile money services – proved exceedingly difficult.

While each of the women eventually obtained the GhanaCard, they shared with us how the registration process was complex, time consuming, and often lacking in transparency.

For instance, Abigail explained, “I had to pay money just to be able to register. I queued for 3 days, and then it took me 3 months to receive the card.” Vida T echoed these sentiments, “It took me four days to complete the registration process and another week to get my ID card. I even had to sleep overnight at the registration before getting enrolled.”

For Vida Q, the delays experienced were considerable, “I had a challenge during the enrolment of the GhanaCard. I was in queue for hours, and after I was enrolled, it took one year for me to receive it.”

To make matters worse, this frustrating and lengthy process can be further exacerbated by unreliable internet across the country – meaning that the women still faced accessibility challenges even after receiving their GhanaCards.

When we spoke, the internet had been out for days due to issues with the undersea cable – a disruption that had immediate and devastating repercussions. The inability to access mobile money can be particularly detrimental to people like the women we spoke to, who survive on what they earn day-to-day.

A lack of reliable service can prevent them from sending and receiving payments, accessing credit, even saving for the future. Ultimately, these setbacks are harmful to the women’s basic ability to support themselves. As Charity shared, “I can’t compete without being able to accept mobile payments.”

Concerns about consent and privacy of personal data collected were also top of mind for these women.

Alongside accessibility concerns, the women also expressed a desire to understand more fully what registering for digital services entails — beyond the surface benefits. “I signed up for mobile money, but I didn’t fully understand what it involved or how my data was being used,” shared Patience.

This lack of understanding – and meaningful consent – became painfully clear when the conversation shifted to biometric data.

The women were particularly concerned once they learned the implications of having their fingerprints, iris scans, and facial analyses collected. As Vida lamented, “I worry about my information falling into the wrong hands.” Without clear explanations and assurances, the mandatory nature of the GhanaCard’s data collection can feel intrusive rather than inclusive.

Ultimately, the lack of access to and agency around their personal data left many of the women feeling disempowered.

Theresa explained, “It is what the government wants, and I cannot object.” Similarly, Abigail reflected a pervasive sentiment of resignation, “Because our leaders think having a National ID card is important, so we, the citizens have no choice in the matter.” Her words, echoing those of her peers, highlight the need for greater transparency in the way they understand – and interact with – digital systems.

When it comes to digital transformation, benefits and challenges often coexist. But there is a path forward.

The experiences of Charity, Abigail, Vida Q, and other women underscore the double-edged nature of technological advancements. On one hand, innovations like the GhanaCard have expanded access to essential services and conveniences that were previously unimaginable, like secure online banking and broad market access. On the other, they have introduced new vulnerabilities and dependencies, where a single point of failure can lead to widespread economic disruptions or concerns of privacy and consent.

These barriers, however, are not insurmountable.

To overcome them, it is essential to promote people-first data practices, including digital literacy, new models for improving consent, and transparent and trusted models for data sharing. Empowering women like Mary, Vida T, and their peers with information about the usage of their personal data, and access to it, is not merely a regulatory necessity — it is a fundamental aspect of fostering an inclusive digital economy.

(*The women asked to only be identified by their first names.)