Claire is a university student about to graduate, submit her thesis, move into a new apartment, and seek her first job. Normally, she would separately apply for tax relief, council tax discounts, energy assistance, or employment support services. Each service requires a distinct application with multiple forms, data fields, buttons, actions, and document uploads—multiple touchpoints. In a different setting, a more proactive government digital service would use artificial intelligence (AI) to anticipate her needs by linking her status as a student to pre-filled applications that use her existing data and transparently guide her through each step. While these proactive services rely on back-end data integration and application programming interfaces (APIs), it’s the design layer that translates those technical capabilities into understandable and actionable interactions for people like Claire.

As governments explore AI for public service delivery, much of the attention remains on regulation, privacy, computing power, and technical considerations. Yet, crucially, the role of design remains overlooked. The ability of a government to design for the digital realm significantly influences the effectiveness of integrating AI into public services.

Good AI-powered government systems are proactive and predictive - but not invisible.

Traditional government services typically involve looking for a specific benefit, reading the requirements, and starting the application through repetitive manual data entry and form submissions. Integrating AI fundamentally shifts this interaction. Claire, preparing to enter the workforce, could receive automatically pre-filled eligibility summaries based on existing government-held data. Her task would become verifying this information rather than entering from scratch. This shift is only possible when interoperable systems make data available and reliable across departments. AI builds on that foundation to personalise and pre-structure service delivery in proactive ways that anticipate needs, rather than to wait for user input. And, as one study has shown, people seem to be comfortable with proactive digital interactions from their governments.

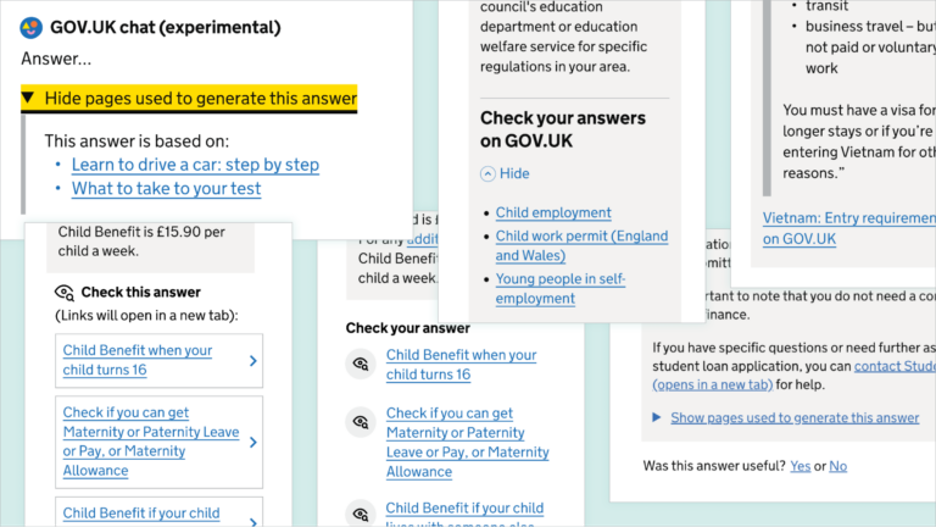

However, for AI-powered solutions to be fully successful, they’ll need to offer the same level of transparency as traditional government systems. What the traditional process allows and asks from us, as users, is to be able to check – for ourselves – eligibility, regulation, departments responsible, and so on. Let’s say that Claire knows or thinks she’s entitled to a tax benefit one of her friends now receives, but the AI system is not suggesting to her that specific tax break. She will naturally seek clear and comprehensible reasons for this omission, and the AI tool needs to provide this information. With an AI-powered system, people will no longer expect that they have to check for themselves. Rather, they will expect the AI tool to automatically provide transparency regarding why it makes specific decisions, suggests some things, denies a particular benefit, or requires additional documentation. AI must not make the government “invisible”, but better at explaining itself.

Digital public infrastructure can be a key enabler for AI.

Design systems, as expressed in my first expert comment, focus on visual standardisation, ensuring that all of the government digital user interfaces look the same. This helps Claire trust that she’s dealing with the actual government. While visual consistency is extremely valuable, integrating AI in public service delivery will demand much broader thinking about how people interact with digital services.

Before moving onto what such a government design layer for the AI era may look like, let’s first establish the connection between AI and government digital infrastructure. Digital public infrastructure (DPI) and artificial intelligence now sit at the center of many government transformation conversations. When combined with DPI, AI can automate, recommend, and anticipate service needs with greater confidence. DPI ensures that the underlying data is reliable, structured, and permission-based. It enforces shared data standards, authentication protocols, and access controls. This creates a secure and auditable environment where AI models can be trained on real data while still respecting privacy, legal requirements, and sector-specific rules. As a result, development cycles are shorter, and the risk of ethical failure is reduced.

Estonia, one of the best known cases of DPI success, demonstrates this integration. Its X‑Road data‑exchange system links almost every national registry, giving developers a single, authenticated interface to authoritative information. Building on this broader DPI environment, the government has pursued a comprehensive AI strategy that includes Bürokratt, a virtual assistant designed to pre‑fill forms, retrieve documents and route enquiries across departments. Once the data layer is established, integrating AI becomes simpler compared to scenarios without a DPI foundation.

For AI and DPI to truly meet people’s needs, good design is crucial.

Suppose a country has achieved this integration (DPI and AI). Then two human‑centred challenges rise to the top: legibility and usability. Citizens will benefit from using AI‑enabled services if they can see what the system is doing, understand why a suggestion appears, and feel confident that they can override it when necessary. These are design – rather than technical – questions. It reminds of the early days of interaction design, when the inventor of the laptop, Bill Moggridge, took home a working prototype only to realise that, despite the breakthrough in portability, the interface was difficult and frustrating to use. In the same way, an advanced AI model connected to a good data exchange system will still fall short if it’s not legible, understandable, and gives people a sense of control.

Governments that have invested in design systems are better prepared to meet this challenge, as they have:

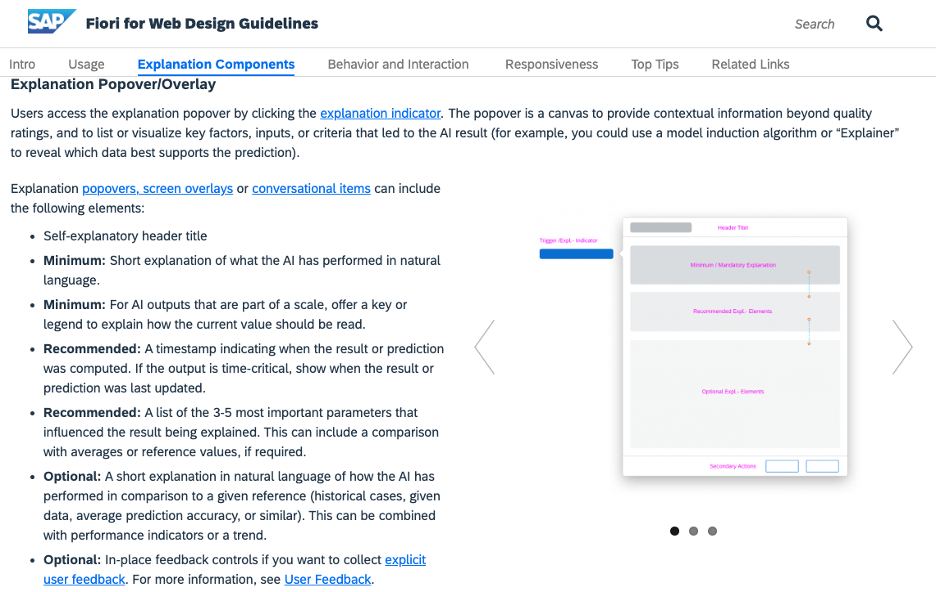

- Clarity on where automation belongs. A well‑maintained design system already maps common service journeys and interaction points where one component or pattern is better than another. Teams therefore know where a proactive “next best action” or an auto‑completed field fits naturally—and where a review or consent step is still required.

- A culture of improvement by collaboration. A federated design system (one collaboratively maintained by teams across departments) ensures teams share good practices, test results, and feedback on interactions enabled by the design system. These practices are crucial when a government is introducing a radically different way to interact with users through AI.

- Flexible service interfaces. A design system brings structure to how interfaces are built, using standardised components and shared patterns that can be reused and adapted. When Claire, our recent graduate, receives a pre‑approved housing benefit or a verify‑and‑submit scholarship application, she is not merely chatting with an intelligent bot. Ideally, she’s interacting with interface blocks that behave consistently and are flexible enough to evolve based on real user behaviour and feedback. This makes it possible to improve AI-enabled services without redesigning them from scratch each time.

As governments increasingly turn to AI-powered systems, collaborative, intentional design is essential for user uptake and trust.

The effective integration of design systems, and practices behind them, requires the participation of multiple stakeholders. This includes everyone from DPI funders shifting attention to design systems as a legitimate layer for investment, to design teams in government who prioritize exploring AI-enabled patterns and AI guidelines for design systems. Design systems and practices are as essential to DPI as data standards or identity layers when it comes to the successful adoption and implementation of AI in government.