As South Africa assumes the G20 presidency – the first African country to do so – it signals a powerful moment for the Global South to shape global economic discourse. The country is looking forward to building on the achievements of past presidencies, by focusing on several issues, including digital public infrastructure (DPI) and digital transformation, building on the work initiated under the Indian Presidency and continued under the Brazilian Presidency. The South African Presidency intends to examine the different aspects of policy, regulation, and data governance required for DPI to be transformational, and I cannot help but unpack this move through a civil society lens.

The growing momentum around DPI in Africa is emerging as a powerful tool to drive inclusion and social and economic transformation. Financial service providers, donors, and governments increasingly champion DPI as the next frontier for development, promoting it as having the potential to support Africa’s digital transformation: connecting communities, expanding access to services and opportunities, and improving public accountability. However, while corporations and governments dominate much of the conversation, civil society remains a crucial but sidelined voice. CSOs often engage in frameworks already shaped by states, donors, and private technology actors, with limited space to influence agendas in a meaningful or structural way. To this end, the South African Presidency’s focus on a DPI approach with common and open standards is critical – as it helps ensure interoperability across and between infrastructures, services, and applications.

With such enormous potential, it’s time to frame DPI in more accessible ways that resonate.

When it comes to promoting CSO involvement in DPI, terminology and framing matter. Where DPI components are framed around tangible issues, like access to identification, digital rights, or internet freedom, CSOs demonstrate strong leadership and activism. Take Sierra Leone, for instance, where the government set out to align stakeholders, including civil society, around its digital transformation agenda under the Digital Economy Program (DEP). In this case, the Digital Impact Alliance (DIAL) played a pivotal role as a third-party convener, supporting the Government of Sierra Leone in the finalization of key national strategic documents, including the National Digital Development Policy, the National Digital Development Strategy, the Government Enterprise Architecture Blueprint, and a National Data Strategy. Through 15 workshops held over 18 months, DIAL facilitated an inclusive policymaking process that engaged over 220 stakeholders, including 25 CSOs. These workshops positioned CSOs as core contributors, allowing them to bring rights-based perspectives that shaped policy provisions on user consent, interoperability, and accountability, ensuring that digital strategies balanced efficiency with equity and human rights protections.

In Zambia, which had already embarked on its DPI journey, the government demonstrated a similar commitment to inclusivity and trust-building. Its efforts were seen in instances such as the strategy and design stage of its DPI life cycle, where the Department of National Registration, Passport, and Citizenship (DNRPC) dedicated resources for shaping robust institutional structures around its digital ID systems. Additionally, in June 2024, led by the Ministry of Home Affairs and Internal Security and designed by UNDP, the government launched the Legal Digital ID Model Governance Assessment. This assessment was specifically structured to include both government stakeholders and civil society organizations, marking a significant step toward shared accountability in digital ID governance.

And, beyond these direct examples, there are also many cases of CSOs already substantively engaging with topics that support a healthy DPI-ecosystem, albeit often under different names or silos. Organizations like Paradigm Initiative, UN Global Pulse, CIPESA, and the Africa Digital Rights Hub have worked extensively on data justice, equitable digital inclusion, and open governance, all themes that are linked with a good DPI approach. However, without deliberate efforts to unpack the concept of DPI, localize it to community experiences, and remove unnecessary technical barriers (such as jargon-heavy policy language or limited access to foundational documents and standards around digital identity interoperability or data exchange protocols) civil society participation will remain fragmented and reactive.

The disconnect is not due to a lack of civil society interest. Rather, it reflects the absence of accessible framing that links DPI to concrete societal outcomes. When DPI is positioned purely as a technological fix, it sidelines the social dimensions that civil society is best placed to address. The impact is twofold: CSOs are less likely to self-identify as stakeholders in DPI initiatives, and DPI implementers are less likely to proactively engage them.

The UN Universal Digital Public Infrastructure Safeguards Framework provides a welcome vision for CSO engagement in advancing people-centered DPI.

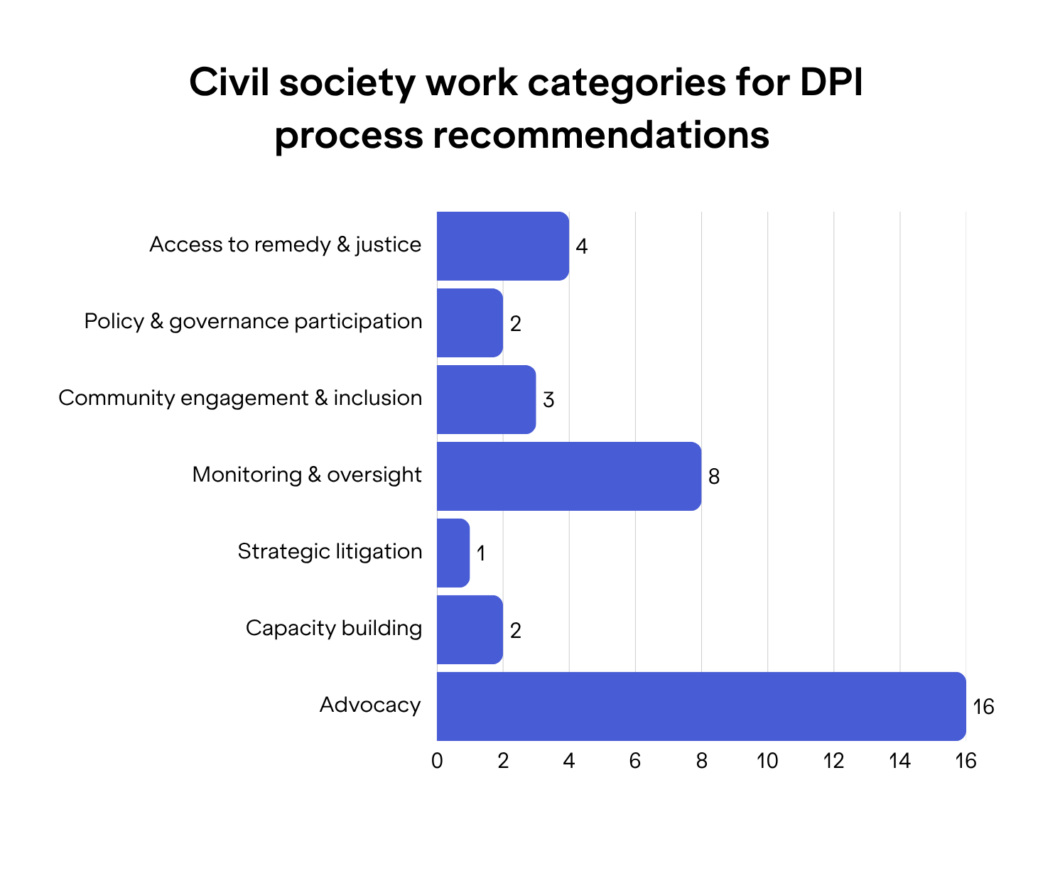

The UN Universal DPI Safeguards Framework offers an outline – and critical test – for increased engagement. The Framework recognizes civil society as ‘’Advocates’’ in shaping, scrutinizing, and sustaining DPI systems. Across the lifecycle of the Framework, and based on the principles, it highlights 33 process recommendations for Advocates – i.e. civil society – that broadly cuts across: advancing rights and inclusion, ensuring accountability, and shaping governance.

The framework lays out a vision for DPI that is inclusive, rights-based, and people-centered. It emphasizes the need to empower individuals and communities to have agency over how they access and use digital infrastructure, ensuring that DPI is governed transparently, accountably, and inclusively – a vision that CSO’s could actively contribute to and help meaningfully shape.

Yet, today, civil society is still often viewed as an afterthought.

Across Africa, CSOs are increasingly involved in policy dialogues, consultations, and governance processes. On paper, this signals progress. But in practice, these engagements often fall short of meaningful participation and fail to reflect the lived realities of communities and CSOs on the ground. The majority of CSO participation in DPI processes remains peripheral – advisory at best, reactive at worst. In the context of emerging DPI ecosystems, particularly around digital ID systems, payment platforms, and registries, many civil society actors are invited to the table only after critical decisions have already been made. By the time consultations are initiated, core choices about architecture, standards, procurement, and partnerships are often settled. This belated inclusion undermines the very safeguards the DPI Safeguards Framework seeks to institutionalize.

This dynamic plays out vividly in practice. Take, for instance, the Framework’s recommendation on strategic litigation. Kenyan CSOs, through organizations like the Nubian Rights Forum, were pivotal in contesting the Huduma Namba digital ID rollout. They raised alarms around privacy violations, exclusion risks, and lack of legal safeguards, resulting in judicial interventions that temporarily stalled the project. Most recently, many of the same concerns resurfaced under the Maisha Namba initiative. While this reflects the formidable power of CSOs to intervene and protect rights, it also points to a troubling pattern: civil society is often forced to respond only after rollout begins, rather than co-design solutions that prevent harm in the first place, a pattern that reinforces digital distrust, exclusion, and inequality.

In Uganda, groups such as the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights, Unwanted Witness, and the Health Equity and Policy Initiative have highlighted the discriminatory impacts of the Ndaga Muntu national ID system, particularly its failure to serve marginalized communities. These organizations are doing vital work, yet they remain largely excluded from formal decision-making mechanisms, an exclusion that stands in direct contradiction to the promise of inclusive governance.

Even recommendations in the UN Universal DPI Safeguards Framework focused on policy and governance participation, as well as advocacy, face serious implementation gaps. In 2020, a coalition of over 60 CSOs, including Access Now, Namati, and the Open Society Justice Initiative, called for greater transparency and public engagement at every stage of digital ID development. This demand came from a recognition that, while CSOs are deeply engaged with issues like privacy, access, and justice, they are still not treated as strategic partners in the design and development of DPI.

When it comes to good DPI, inclusion matters - especially in fostering legitimacy, trust, and sustainability.

Incorporating civil society meaningfully into the DPI lifecycle would enhance the legitimacy of decision-making, foster citizens’ trust, and lead to stronger, more sustainable outcomes. Greater engagement requires a shift in mentality from a strategy centered on one-way communication where public authorities notify the impacted population about their unilateral decisions on the details of the DPI project, to a more active engagement based on a two-way interaction between people, who can be represented by CSOs.

For instance, the international community has developed the Principles on Identification for Sustainable Development, with more than 30 organizations having endorsed this set of shared principles that are fundamental to maximizing the benefits of identification systems for sustainable development while mitigating many of the risks.

In 2020, South Africa initiated a series of community consultations aimed at reforming its national identity system to promote greater inclusivity. These consultations revealed key exclusion challenges within the existing system, particularly for nonbinary and transgender individuals, who were marginalized due to the use of gendered identification numbers and the lack of mechanisms to amend sex assigned at birth. Concerns were also raised about the exclusion of abandoned children from civil registration, stemming from the requirement to provide parental identification details at the time of registration. In response, regulatory reforms have since been introduced to address these barriers to accessibility and inclusion.

Additionally, organizations like the European Digital Rights Network (EDRi) have paved the way for civil society in European countries to get a seat at the table in EU debates, policy, and lawmaking. Through successes such as modernizing the European data protection framework, and working to mitigate the negative consequences of data retention and other forms of surveillance, EDRi’s collective action and expert input has increased the visibility and influence of civil society in EU debates.

So, how might we reframe the conversation around DPI?

To unlock the full potential of DPI in Africa, we must reframe it not as a narrow technical endeavor, but as a deeply political, social, and economic project. This requires broad-based participation and shared ownership. Civil society must not be confined to reactive roles or symbolic consultations. They must be empowered to co-create, challenge, and reject digital infrastructure models that do not align with the needs and realities of their communities. Anything less risks reducing DPI to a technocratic exercise that deepens social fragmentation and perpetuates structural exclusion.

Watch for the next article in this series, where we will critically examine the UN DPI Safeguards Framework’s principles against the real-world experiences of African civil society actors and their efforts to influence DPI development.